Search

You searched for articles ...

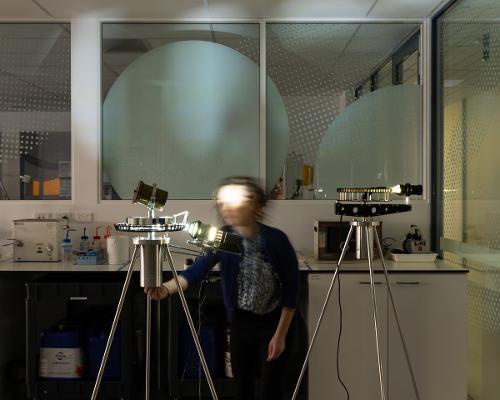

On the 15th of June, 2023, students from The Australian National University’s School of Arts and Design hosted a funeral and memorial service to celebrate the life (and death) of Photography at PhotoAccess, Canberra.

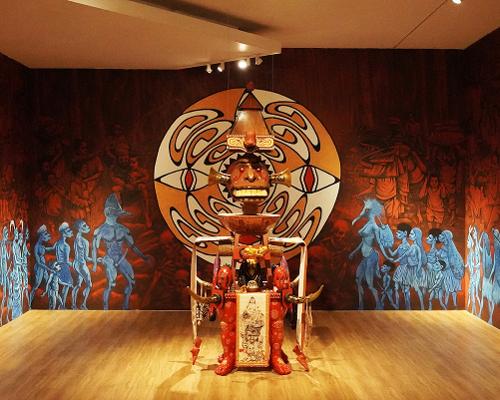

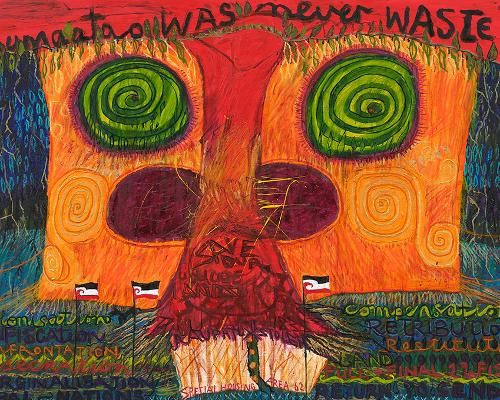

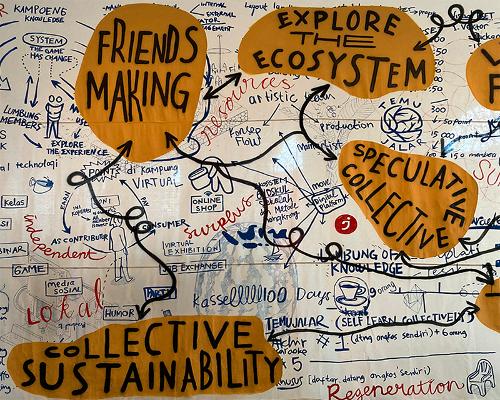

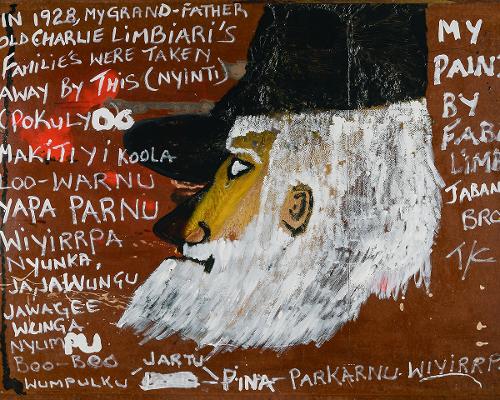

In the rapidly expanding literature on the Tennant Creek Brio, writers have touched upon a decidedly ‘masculine’ quality in the group’s work. John McDonald calls the Brio’s work ‘incredibly aggressive’ and ‘raw’ and ‘wild.’ Erica Izett, the Brio’s regular curator and greatest advocate, refers to their work as a form of insurgent ‘guerrilla theatre.’ These masculinist tendencies should be of little surprise. The Brio started in 2016 as an art therapy group as part of Strong Men, Strong Families through funding from the Anyinginyi Health Aboriginal Corporation facilitated by painter Rupert Betheras. It grew to have about twenty men involved before moving to the Nyinkka Nyunyu Art and Culture Centre in 2017, where it was declared an artist collective.

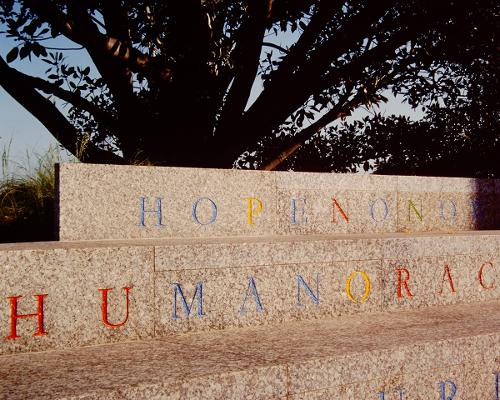

All struggles are essentially power struggles. Who will rule, who will lead, who will define, refine, confine, design, who will dominate. – Octavia E. Butler. Some struggles are invisible simply because a single word is missing from public discussion. I find that this is particularly the case with words that carry life-giving concepts and that challenge social hierarchies. Their absence can give clues to who might be excluded and what is considered of less value within a given society. One such word is ‘neurodiversity’, and it is missing from exhibition records within some of Aotearoa New Zealand’s leading public art galleries.

In a sparse gallery space, a detached hydraulic door closer lies splayed on a white panel. This unassuming readymade by Belgian artist Steve Van den Bosch provides a subtle topographical deviation on the dull cement floor. Titled Assistant (2021), the closer was relocated from the gallery director’s office for the duration of Round About or Inside (30 September 2021 – 20 November 2021) at Griffith University Art Museum, Brisbane. Appropriately placed on the ground—the anti-art/anti-functional gesture par excellence—the artwork suffices as a miniature monument to technologies of access, reflecting on how we move through spaces and what mechanisms exist to ensure our safe and comfortable journey, to welcome us, or to deny us entry.

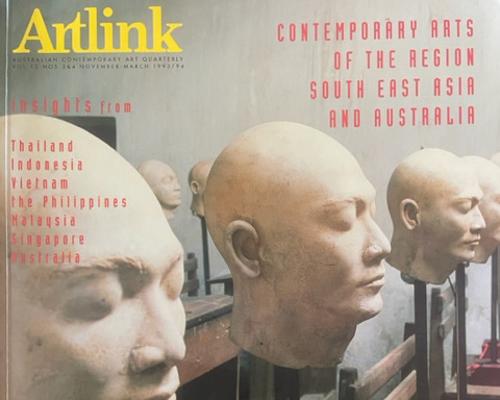

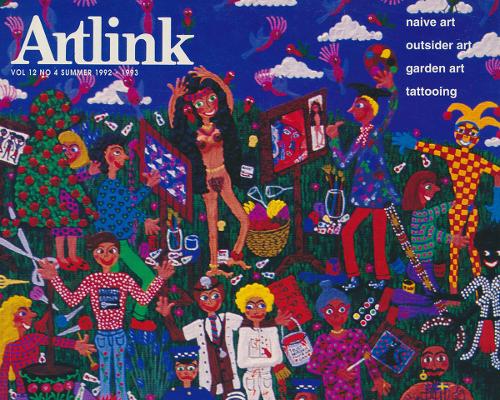

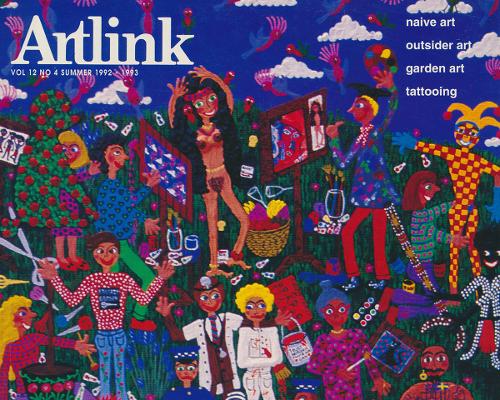

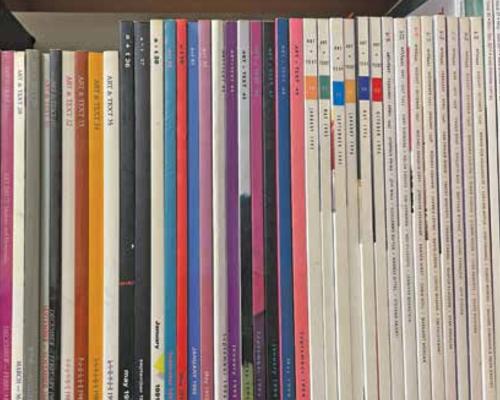

Founded in Melbourne by Paul Taylor in 1981, the Australian art magazine Art & Text began the same year Stephanie Britton founded Artlink in Adelaide. During the 1980s and 1990s, Art & Text made global waves. From its earliest issues, it infused art criticism with critical theory when that very notion was radical and fresh in Australia. By his mid-twenties, Taylor had curated POPISM at the National Gallery of Victoria (1982), edited the landmark volume Anything Goes: Art in Australia 1970–1980 (1984) and had moved to New York to become a renowned critic for Vanity Fair, Flash Art and The New York Times.

In an essay discussing art criticism and the pain it can inflict, the European critic Jan Verwoert reflects on the way most writing on contemporary art has sublimated its brutality or—some would say—its honesty: The main reason for the polite tone in art criticism [...] is that—contrary to the distance that, for instance, separates the opera critic from the social milieu of the orchestra musician—art critics and artists mingle in the same milieu. There is no stage between them. It’s impossible to deny that you are part of the same living social community when the artist you just wrote badly about is also someone you are bound to soon run into again at the next opening in town ...

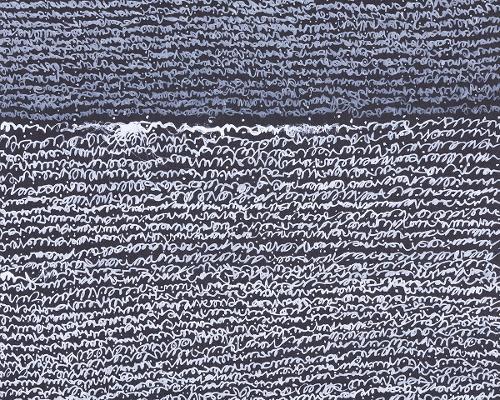

Ngami-lda-nha / looking

In our past/present/future continuum, we can look simultaneously to the potential of what is and what can be, acknowledging that what we are currently seeing and experiencing is also that which is ‘not yet’. Friend and fellow Gamilaroi Countryman Joshua Waters speaks to the sight/foresight of our ancestors through a story of Garruu Winangali Gii/Uncle Paul Spearim, pointing out to him a barran/boomerang in a tree. Joshua recounts how he spent minutes ‘foolishly looking …for a literal boomerang’, only to realise later that what Garruu was talking about was the ‘future potential state’ of a particular branch that had the perfect curvature from which to shape a barran. Looking to the future, in the now, we also acknowledge and deeply winangali/listen/understand/respect the past work and words of other Blak artists, authors, and thinkers who have generously shaped and progressed what is—in terms of Indigenous art and art criticism, our ongoing agitation for autonomy, agency, and the re-centring and de-homogenising of our art practices amidst constant mainstreaming pressures and perspectives.

_Card.jpg)