I climb the stairs in the rear corner of the University of Queensland Art Museum and there awaits George Tjungurrayi’s Tingari (2004), a depiction of the Tingari cycle, an ancient story mapping sacred sites and following ancestral creation routes across Pintupi homelands. Tjungurrayi’s shimmering geometric field of interlocking black and white stripes shift and sparkle as my eyes traverse the surface. The act of looking—focusing and refocusing—feels decidedly physical in the face of this dazzling composition, which depicts the sacred energy fields of Tjungurrayi’s Country. For me, this painting functions as a visual reminder of Tony Birch’s assertion that 'Indigenous sovereignty persists regardless of the impositions of colonisation'—and all the destruction that it wreaks.[1] Positioned at the beginning of We Are Electric: Extraction, Extinction, and Post-Carbon Futures—which probes the uses and abuses of this planet’s natural energy sources—Tjungurrayi’s painting foregrounds the inextricable links between Aboriginal modes of care, land rights and politics.

© the artist licensed by Aboriginal Artists Agency Ltd.

We Are Electric curator Anna Briers brings together works by fifteen artists and collectives from across the globe. The result is a cacophony of discursive voices responding to a common thread, or threat; voices which, at times, literally bounce off one another across the two levels of the museum. Responses from those on the frontlines of colonial/climate/capital chaos are set amongst perspectives from others observing more comfortably from the wings. Jack Green’s painting Desecrating the Rainbow Serpent (2014), for example, shows the destruction of his home (the resting place of The Rainbow Serpent) by Glencore’s McArthur River Mine and the subsequent deaths of many Gudanji, Garrwa, Marra, and Yanyuwa people who rely upon this sacred place for spiritual and physical wellbeing.

Conversely, Elise Rasmussen’s In the Valley of the Moon (2022) juxtaposes video recordings from field trips to the lithium rich salt flats of the Atacama Desert (Chile) and the Tesla Gigafactory in Sparks (Nevada, USA) while narrating the pitfalls and paradoxes of so-called green energy futures. Rasmussen speaks of complicity in a flat monotone: 'I want to take the stones; I want to possess; the desire in me to keep is part of the whiteness that flows through my bones'. For me, a white non-Indigenous migrant-settler living on Aboriginal lands, this stimulates a moment of critical self-reflection which, in turn, highlights the exhibition’s lack of acknowledgement of racial injustice at the heart of the global climate crisis.

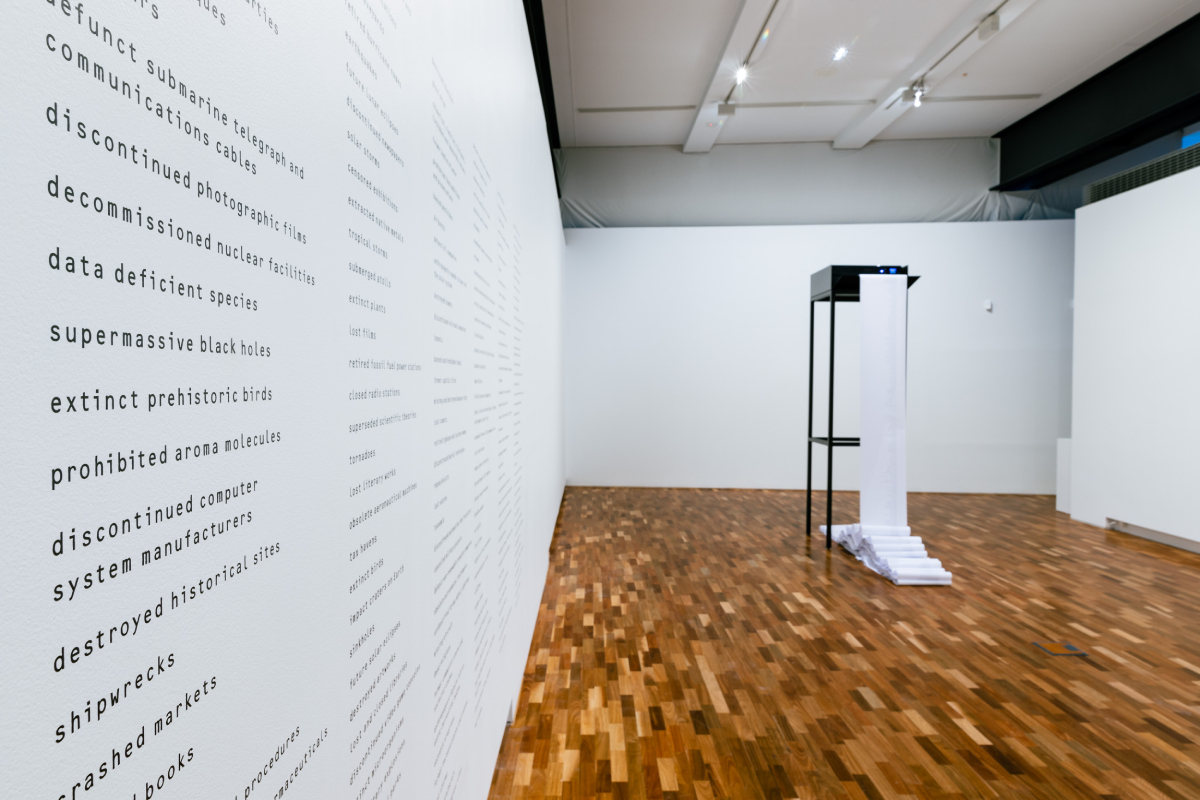

The long-term industrial-scale energy fetish at the centre of this exhibition brings dire consequences, and as Megan Cope’s Untitled (Death Song) (2020) and Dane Mitchell’s Post Hoc (List of Lists) (2022) show, there is much to lose. Cope’s installation consists of oil drums, giant drill bits, and rocks scavenged from blasted landscapes rigged together with strings from pianos and violins staging musical instruments awaiting a scheduled apocalyptic lament. Mitchell’s work features a printer on a raised platform which spills forth a continuous list of millions of vanished, absent, obsolete, lost or redacted things. As I approach the paper cascade, the printer grunts and ejects a long list of lost supernovas. I feel almost breathless attempting to accept the enormity of the destruction and wastefulness suggested by this inventory.

Despite the grim outlook the exhibition reminds me—as the title suggests—that I too am electric. I am alive: pulsing with flows, rhythms, vibrations, and the capacity for connection. In their video montage Metamorphosis (2020), The Institute for Queer Ecology insists that desire is the primary tool for world-building. They suggest, energy-wise, we could equate one barrel of crude oil with the kinetic energy of a flock of doves flying, or a person falling in love. Zany associative thinking of this kind leaves me open, unguarded, and receptive in much the same way humour does. I am captivated by Diane Borsato’s Gems and Minerals (2018), a video featuring museum guides responding in American Sign Language to crystals and rocks in glass vitrines at the Royal Ontario Museum (Toronto). I read the subtitles and contemplate: 'there are facial oils and fingerprints on the glass/are our bones and teeth rocks?/unprocessed silver ore attracts bats/everything alive wilts and fades, but we try to hold onto it forever'. At times delightfully hyperbolic and at others sincerely elegiac, the guides communicate alongside the specimens to produce a narrative that uses and refuses the limitations of the museum’s conventions.

According to the curatorial claim, We Are Electric is a call to think (and act) beyond petro-capitalism, in sympathetic resonance and solidarity with planetary and non-human systems. Importantly, alongside this call to think and act, the exhibition is also a call to feel. It asks the body to seek connectedness to people, creatures, and Terran lifeforces; to care and delight, to love and grieve. It stimulates responsiveness to the challenges afoot through creative evocations of grief, playfulness, desire, and what Donna Haraway calls 'sympoesis' or ‘making with’.[2] This is plain in Eglé Budvytytè’s Songs from the Compost: mutating bodies, imploding stars (2020) a film featuring non-binary bodies slipping, contorting, or ‘collapsing with’ the Curonian Spit (Lithuania), a UNESCO World Heritage Site. Watching this process, I wonder what it would feel like to be the earth; what it would feel like to be a ravaged planet? Perhaps this is too great an imaginative leap to take. Or perhaps, as Tjungurrayi’s Tingari forewarned, these are the kinds of empathetic gestures, modes of care, or cosmological views that must be prioritised if the world and its diverse energetic lifeforces are to continue.

Footnotes

- ^ Tony Birch, “Our Red Sands Dug and Sifted: Sovereignty and the Act of Being,” in Sovereignty, exh. cat., ed. Paola Balla and Max Delany (Melbourne: Australia Centre For Contemporary Art, 2016), 17.

- ^ Donna Haraway, Staying with the Trouble: Making Kin in the Chthulucene (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2016), 58.