Since his death in 1993 conceptual artist Ian Burn’s art historical status in Australia has grown considerably, but he has never been more than a marginal figure in Europe. This is set to change with Ian Burn at the MAMCO Geneva (Musée d’Art Moderne et Contemporain), Switzerland’s biggest museum of contemporary art. The first solo exhibition of Burn’s work outside of Australia, it’s also the first fully-fledged survey of his mature work anywhere.

Ian Burn spans three decades, starting with the minimalist and conceptual art made in London then New York between 1965 and 1970. It tracks the evolution of his practice as a member of Art & Language (A&L), his ostensible departure from the art world after returning to Australia in 1977, and his landscape-text paintings of the late ’80s and early ’90s which marked his return to art making. Surveying Burn’s artistic contribution to minimalism, conceptualism and postmodernism, and placing the art alongside his activism and writing, the exhibition constructs a developmental narrative that reveals the diversity and the continuity of Burn’s oeuvre.

The exhibition is curated by Dr. Ann Stephen, an art historian whose tireless research on the artist has yielded important exhibitions as well as the acclaimed 2006 monograph Looking at looking: the art and politics of Ian Burn. The foremost expert on Burn, her work has ensured his continued relevance to modern and contemporary art discourse in his country of origin. For those familiar with Stephen’s projects and other existing research on Burn, there aren’t many surprises to be had in Geneva. But this exhibition isn’t meant for antipodean viewers; it’s a curatorial export addressed to a European audience, one that recognises Burn primarily for his collaborative contribution to a conceptual art collective in the 1970s yet remains largely unaware of his work as a solo artist.

To underline Burn as a discrete author, Stephen’s exhibition adopts the format of a linear chronology typical of a museum retrospective. The first room features three canvases painted in London in 1965 and ’66; the oldest, Re-ordered painting no. 2 (1965), is a multicoloured geometric abstraction with stencilled numbers. The point of the work, Burn observed at the time, was to disrupt the ‘“natural” and hierarchical order in which we see the forms within a painting’ through the superimposition of a numerical sequence or ‘artificial order,’ the conflict between them initiating a kind of self-reflexive viewing.[1] The numerical tagging of the colour-forms evokes an art theorist’s diagram, rerouting the spectator’s gaze around the work with analytical intent.

The second room tracks the intensification of self-referentiality in Burn’s work following his arrival in New York in August 1967. Mirror piece (1967) is a framed mirror hung alongside thirteen pages of typewritten notes and diagrams documenting its perceptual, physical and conceptual properties. The mirror looks like a ‘readymade’ but was constructed by the artist using materials and techniques from his day job as a picture framer. From the meta-commentary we learn that slotted in front of the mirror is a pane of transparent glass, hence our perception of the still-paltry object isn’t what it seems.

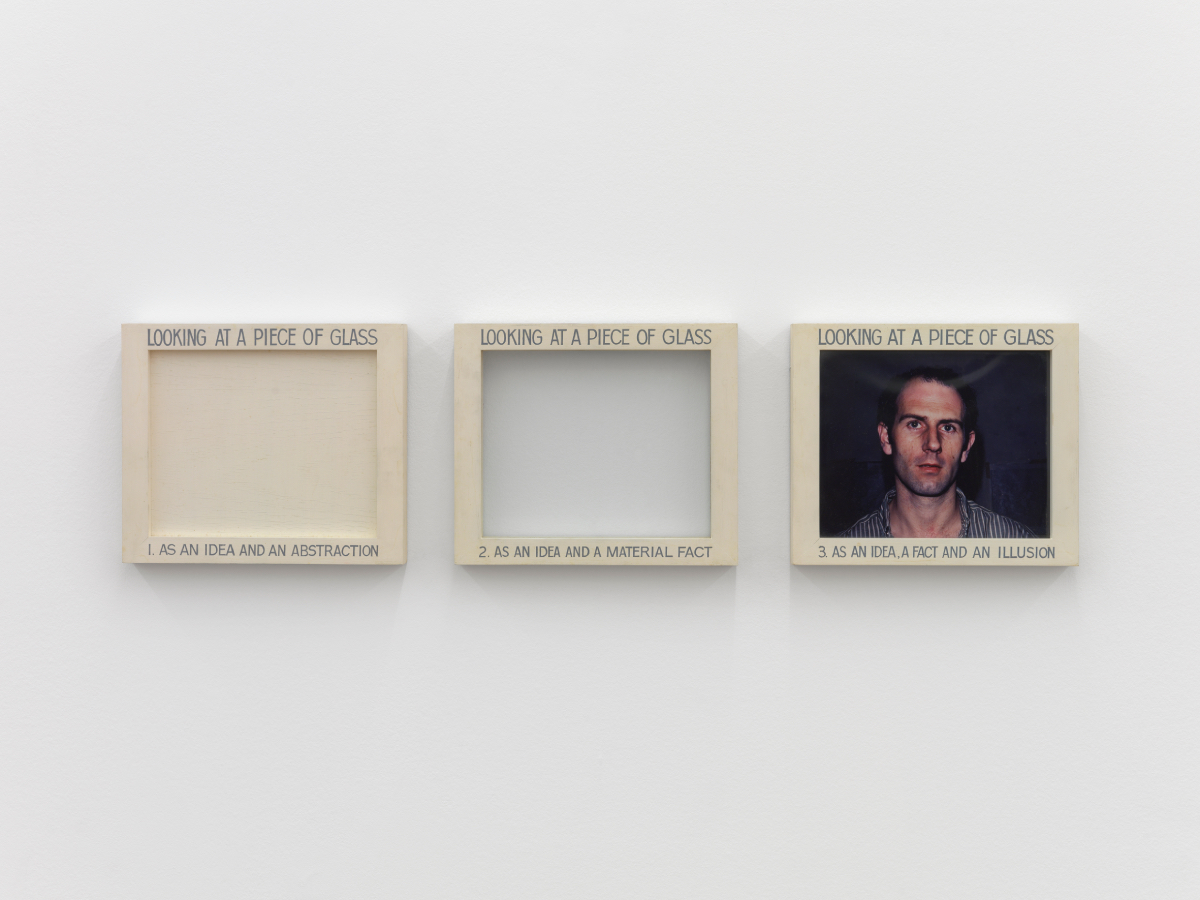

Mirror piece is one of several in this room that together constitute a dialectic of reflection and transparency. In Undeclared glasses (1967), two glass sheets are leant against the wall beside a text discussing their uncertain aesthetic status. Painted on the mirror glass of No object implies the existence of any other (Hume’s mirror) (1967), Enlightenment philosopher David Hume’s words appear to describe the flow of reflections across the picture surface. In Looking at a piece of glass (1967–68) the banal title is repeated across the top of three frames, along the bottom of which are captions describe the differing contents inside each: a backing board painted the same cream colour as the frame (‘1. as an idea and abstraction’), an empty frame through which the wall is visible (‘2. as an idea and material fact’) and a photograph of the artist staring back at us (‘3. as an idea, a fact and an illusion’). Of course, looking ‘at’ transparent glass is near impossible: one instead looks ‘through’ or ‘around’ it. I found myself inspecting the work’s dated decorative elements: hand-painted type, manilla folder coloured cream frames, nocturnal headshot of the artist with five o’clock shadow in striped shirt. Decoration subsists despite Burn’s efforts to negate it, a pleasurable distraction from the Wittgensteinian game played out in the work.

The logic of tautology is fundamental to conceptual art’s ‘aesthetic of administration’, as art historian Benjamin Buchloh argued, and few explored it as single-mindedly as Burn. By incorporating surface reflections into the artwork—a ploy that can be traced back to the patterning of varnishes and glazes in Burn’s London paintings—the tautology is turned inside-out: context enters the work. Standing before one of the shiny car-paint monochromes Burn made after arriving in New York, the spectator confronts their own reflection in the room. At MAMCO this also means confronting reflections of Burn’s other late ’60s works: photocopies of Australian suburban scenes, a droll essay about crossed-out thesaurus pages by his friend and collaborator Mel Ramsden, photographs of Carl Andre and Sol LeWitt sculptures in New York museums. To look at Blue reflex (1966–67) is thus to examine its exhibition context.

It is unsurprising that Burn was active in shaping the exhibition context for his own work. The curatorial precedent for the presentation of Burn’s late ’60s solo work at MAMCO is undoubtedly Ian Burn: Minimal–conceptual work, 1965–1970 (1992–93) at the Art Gallery of Western Australia (AGWA) that travelled the east coast of Australia. While curated by John Stringer, the exhibition was largely orchestrated by Burn—who negotiated with dealer Peter Bellas the purchase of fifteen works by AGWA which formed the crux of the exhibition; Burn also wrote the project outline, oversaw the hang, and edited the catalogue. The goal of that exhibition was no less than Burn’s invention as a significant artist distinct from A&L with a biographical and stylistic narrative of his own.

There is substantial overlap between the 1992 AGWA and the 2023 Geneva shows: both plot Burn’s work on a linear timeline and make a case for its historical significance to uninitiated audiences. A notable difference between them, however, is their starting point. The 2023 show starts with the London paintings in 1965, whereas the 1992 show included a few earlier Melbourne paintings—Sidney Nolanesque suburban beach scenes and Klee-like hieroglyphic abstractions—to frame his conversion in England from Antipodean modernist to mathematical minimalist.

Ian Burn includes none of these early Australian pictures, which would afford insight into Burn’s practice prior to his first-hand encounter with European and American contemporary art. Given the objective here is to raise Burn’s European profile, tracing the regional prehistory of his minimalist and conceptual art would powerfully illustrate its specificity and in so doing differentiate it from an artist like François Ristori, a solid B-tier proponent of European systemic painting whose experiments with colour, shape and pattern are presented in an adjacent room at MAMCO.

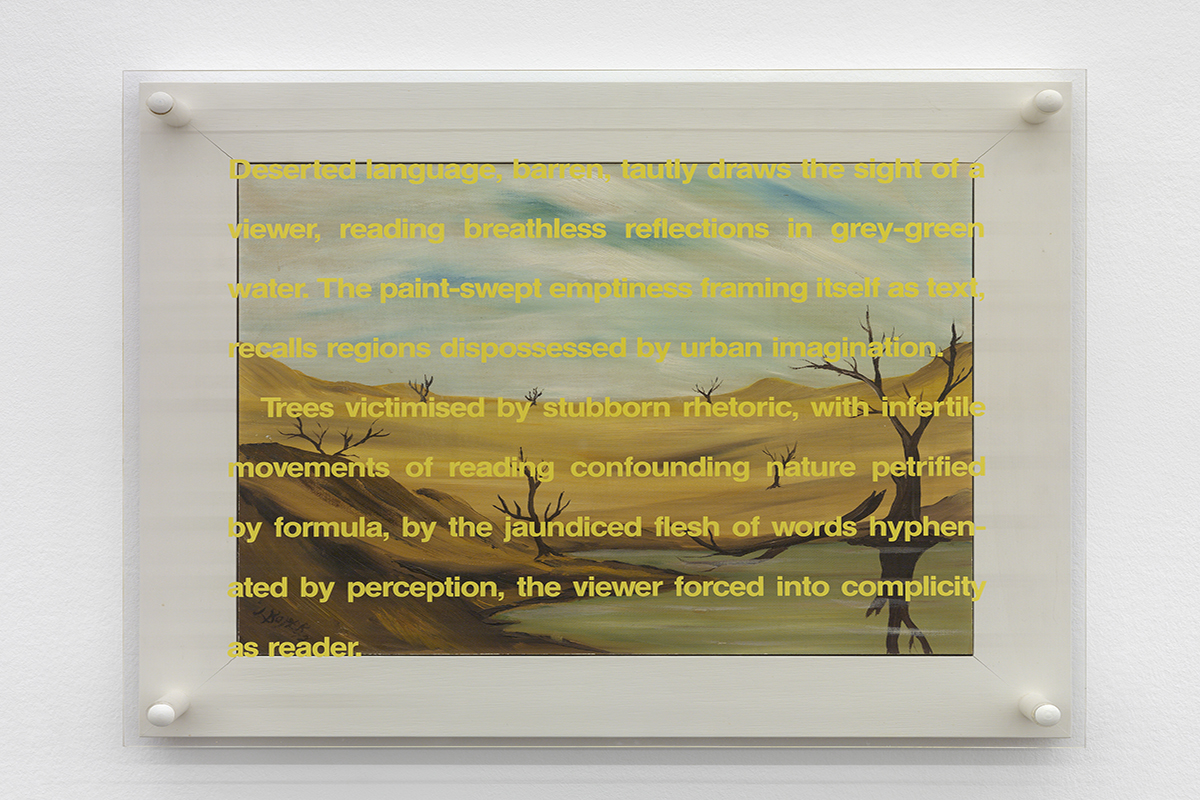

The addition of Burn’s early work would also plot a more meaningful backdrop for the final two rooms. The pick of these rooms is the ‘Value added’ landscapes (1992–94), nostalgic hybrids of conceptualism à la Looking at a piece of glass and landscape painting, the latter an oblique nod to the artist’s own Geelong watercolour landscapes of the late ’50s. The paintings in the ‘Value added’ landscapes weren’t made by Burn—they are amateur works found in op shops that he framed behind a sheet of text-covered plexiglass, the texts alternately describing the paintings, rehashing clichés about the Australian landscape, meditating on the landscape genre and speculating about the relation of text and image.

By the time of the ‘Value added’ landscapes, Burn was a legendary conceptual artist in the wilderness of postmodernism. Spurred by a new generation’s enthusiasm for his two-decade-old art, his attempts at appropriation are stifled by fatherly cleverness. Still, the ‘Value addeds’ are superior to the dainty-landscape-as-general-aptitude-tests Artists think and This painting would be better (both 1993). European viewers unfamiliar with the Australian landscape tradition won’t be the only ones not to ‘get’ these over-mannered works which and bereft of the nihilistic harshness of first-gen conceptual art.

Pastoral quasi-paintings aren’t the only way the artist harked back to his youth in middle age. A wall text at MAMCO states that Burn’s writings from this period ‘on Minimalism and Conceptual art were prescient in reconsidering the relations between visual perception and language’. More remarkable though is the way that Burn’s writings, both autobiographical and art historical, laid a discursive context for the reception of his minimalist and conceptual art. In 1988, when Burn embarked on a series of lectures at galleries and schools reflecting on his life and art of the 1960s, his career pre-A&L was largely unknown. Burn’s motivations for writing about his art were surely complex, but the timing suggests a connection to the AGWA acquisition and then-forthcoming exhibition mentioned above. When questioned by British art historian Charles Harrison about his apparent ‘concern’ for his ‘place in history,’ Burn defended his decision to write about this body of work: ‘are you saying that, as an artist, it’s not my job to take responsibility for my own “history”?'[2]

The task of self-historicisation was pressing for Burn; he hinted at its importance in published writings. The title of his 1985 article ‘Is art history any use to artists?’ invokes the instrumentalisation of art history. Three years later he wrote that ‘artists survive beyond their art through art history, so histories still have to be written as if they mattered, a matter of life and death.’[3] A more explicit meditation on the ‘special effects’ of belated historical construction—pertaining to an object in a gallery—surfaces in a 1990 text about Soft-tape (1966), a work installed at MAMCO:

Status ‘as history’ grants art a reality enhanced by self-sustaining fictions, by immunity to criticism, interpretation not for interpreting. Its reconstruction here translates Soft-tape into fiction. Or parody. What you get is something to point at, historical artifice, only the ideas have yellowed and cracked.[4]

Soft-tape is an installation of a tape-recorder emitting a near-inaudible track of a male voice (Ramsden’s) muttering abstrusely about the process of translating information from one context to another. Made in London for a 1966 exhibition in Melbourne, the work was meant to problematise long-distance communication, but wasn’t shown until twenty-three years later at the 1990 Sydney Biennial, where it registered the spatial but also the temporal gulf between production and exhibition. Unaccompanied by the artist’s framing text, in Geneva the work isn’t identified as a reconstruction but as a genuine artefact of the mid ’60s. Which it is, but also isn’t. Without the text, Soft-tape’s historicity is unproblematised, Burn’s role in the remaking—or making—of the work disappears.

What else has been made to disappear in Geneva? Burn implied that an artwork’s conceptuality is subject to the vicissitudes of time. ‘Yellowed and cracked’ was also a furtive allusion to the physical decrepitude of his own late 1960s paintings after two decades in storage. Rolled up in cardboard tubes and sent to Ramsden's mother's house in Williamstown, many of the London works had degraded, the paint peeling and flaking off the canvases as they were unfurled. The problem warranted its own labour of ‘historical artifice’: restoration and replication.

The story of Burn working on his minimalist and conceptual art in the late 1980s and early ’90s is shrouded in mystery. One can only speculate about why it doesn’t feature in the official narrative of Burn’s art propagated by friends and representatives of the estate. It would not be unreasonable to presume that such news could damage the value of the estate; after all, the market prizes authenticity even in the reproducible forms of minimalism and dematerialised relics of conceptual art. ‘Originals’ and early versions are preferred by collectors.

.jpg)

If Burn’s restorative and replicative labour appears clandestine, this is due more to its avoidance in the literature and museum registries than any concerted effort by the artist. In correspondence with AGWA in 1987–88 Burn freely discussed the restoration as well as replication of damaged, fragile and inaccessible works. He wrote of ‘reconstructions (to be displayed as reconstructions),’ ‘works which are readily replicated,’ ‘travelling replicas’ and ‘special versions;’ he claimed to ‘like the idea of doing an exhibition which has very few ‘original’ works in it and is largely reconstructed—and for this to make no difference to the art.’[5] It made no difference, he thought, due to what philosopher Nelson Goodman would term its ‘allographic’ character: the taped lines and smooth surfaces of one of his artworks contains no ‘autographic’ marks and hence can be copied without degradation, the copy identical to the original.

Burn’s argument that the artwork resides in the idea, not the object, wasn’t concocted belatedly: it was foundational to his minimalist and conceptual art. In 1966 he wrote of ‘concentrating on the pure idea or concept to a point of denying any physical qualities whatsoever. The act of painting my pictures is so simple I could instruct someone else to paint one over the telephone.’[6] Burn put this thought into action two years later when he sent instructions from New York to Melbourne for the fabrication of two Mirror pieces. ‘Idea leading—object following,’ Burn explained to curator Mary Eagle twenty-five years later as they negotiated the Canberra National Gallery’s acquisition of several late ’60s works, including a new ‘version’ of Blue premiss no. 2 (1966–67).[7] He wasn’t alone in thinking this way; the mass-reproduction of minimalist art in the 1980s undertaken by artists, dealers, collectors and museums was justified in broadly similar terms. Burn’s productions at the end of that decade—whether replicas, reconstructions or versions—are part of the afterlife of minimalism and its critique of authenticity.

The temporality of such work is missing from the timeline of Stephen’s Ian Burn, which discourages interpretation of the artist’s agile manipulation of the codes and objects of art history.[8] ‘Formalise’ box (1968) is the only listed ‘replicated version’ in Geneva. One wonders how many versions of Hume’s mirror and Blue reflex materialised in the late 1980s and early ’90s, and whether the datedness of Looking at a piece of glass, its frames closely resembling certain Value-added landscapes made a quarter-century later, truly reflects its physical age. Further research is necessary to understand how the artist’s reconstruction of the past was not only carried out discursively and institutionally: it took brute material form.

Where Burn’s multifarious involvement in the arrival of his minimalist and conceptual art as history might have been documented in Geneva is Les Archives, a vitrine presentation of his writings and printed matter from 1966 to 1993. This post-mortem doesn’t happen; instead, a mass of information conveys the heterogeneity of Burn’s published output. Here well-known art history books, exhibition catalogues and conceptual art journals are presented alongside rare items such as trade union rags from the curator’s personal collection. Alongside a 4 May 1987 issue of The metal worker is a draft version of the notes for Mirror piece covered in Burn’s handwriting. Burn fanatics will enjoy this stuff.

Beyond its inclusion of such niche material, the archive room serves to give a general sense of some of Burn’s activities during his decade-long break from object-making. It goes to filling-in the gap in the exhibition chronology between Burn’s late works of the late 1980s and early ’90s and the single-room presentation of Burn’s ’70s works with A&L. (The latter consists of a video of Burn intoning Marxist lyrics over a Mayo Thompson twelve-bar jam, a row of pseudo-propagandistic posters, a wall of framed annotated Artforum pages and a poster critiquing the glib curatorial importation of Latin American art into the Big Apple.)

Les Archives is eccentrically sorted, incomplete and ultimately inaccessible. Behind glass the publications cannot be read, leaving visitors to glean information from dustcovers and front pages—a somewhat unrewarding experience. Yet this display of the print remnants of Burn’s extra-artistic activities was likely intended as a visually complement to the forthcoming Ian Burn: Collected writings 1966–1993, a 768-page tome edited by Stephen around which she appears to have conceived the exhibition, but publication of the book has been delayed. Evidence of the interrelation between the exhibition and the forthcoming book is their shared date range and the similarity of press release and blurb.[9]

The joint conception of exhibition and book explains the exclusion of Burn’s early Australian pictures and the sparse wall texts in Geneva. It may also explain the ‘replicas, reconstructions and versions’ curatorial method of an exhibition which, exempting the archive room, is basically a hybrid of two past exhibitions: the 1992 Ian Burn: Minimal–conceptual work and Stephen’s survey of Burn’s Late works (1996), the latter incorporating background material such as A&L's and The Red Krayola performance video installed beneath The shouting man posters (1976), in the same formation as the current show. These factors, along with the blank eponymy of the title, generate the impression not of a retrospective but a grab-bag of works available (most are drawn from the estate), that the book might have stitched into a more coherent whole.

At the far end of the third floor of MAMCO, between the A&L presentation and the room of printed matter is the Apartment, a recreation of the Parisian collector Ghislain Mollet-Viéville’s flat decked out with canonical mostly American minimalist and conceptual art of the 1960s. A permanent fixture at MAMCO since it opened in 1994, the Apartment immortalises the site where the tanned, blonde, designer-clad collector carried out his work as an ‘agent d’art’ between 1975 and 1991, living amidst and promoting his collection in photographs that show him posing between artworks and fashion models.

Burn is already part of this glamorous history. In the background of a 1976 image of the apartment Mirror piece is seen cramped into a hallway. Conceived as a radical zero-point of painting, at Mollet-Viéville’s pad, the work may have functioned as a portal for self-contemplation, a useful object in the collector’s re-presentation of lifestyle as aesthetic form. Now in MAMCO’s collection Mirror piece is in the 2023 exhibition, with two seldom-exhibited Burns taking its place in the Apartment. Dissipated mirror (1969) is a hinged construction hung in a corner, a mirror on one wall fastened to an enamel-smeared canvas on the other—a grungy, painterly anomaly of Burn’s proto-conceptual production. On a nearby plinth is the artwork-cum-Duchampian trinket Burn made for Ramsden, ‘Formalise’ box (1968), a pink wooden container on a stand that holds nine sheets of glass which remain invisible despite four ‘viewing’ holes. The verso text lists ‘thirteen anagrammatic permutations on the first word of the title, ending in the phrase “FOUR MEL EYES,”’ a cryptic memorial to the duo’s intense and in-the-1960s-largely-private dialogue.[10] In writing about Burn’s work it is easy to get lost in the artist’s own clearheaded writing about it, but this work is evidence of the pleasure he took in withholding information and obstructing the spectator.

The old rue Beaubourg apartment advertised the tasteful accumulations of its owner; it aestheticised the commodity worship of minimalist and conceptual art. That was Mollet-Viéville’s innovation: to present collecting as analogous to the production of art. Thus, in its replication The Apartment is canonised as both a landmark of late-twentieth century collecting and an installation that engulfs visitors in rooms of blue-chip real estate. And just as artists look to the canon for inspiration, so too do collectors. Amidst the treasures of this faux-domus Burn’s works are encountered as certified expressions of good taste, benchmarks for evaluating one’s bounty. Unlike the pieces in Mollet-Viéville’s collection, these works are yet to find a home.

Footnotes

- ^ Ian Burn, 'Notes, London, c. 1965-66,' n.p. Ian Burn archive.

- ^ Ian Burn letter to Charles Harrison, 9 September 1988.

- ^ Ian Burn, ‘The re-appropriation of influence’ (1988), in Dialogue (Sydney: Allen & Unwin, 1991), 213.

- ^ Ian Burn and Mel Ramsden, ‘Soft-tape, 1966’, The readymade boomerang: certain relations in twentieth century art. The 8th biennale of Sydney, 1990 (Sydney: Biennale of Sydney, 1990), 282.

- ^ Ian Burn letter to Seva Frangos, 24 July 1988.

- ^ Ian Burn letter, May 1966. Ian Burn archive.

- ^ Annotation next to Blue reflex illustration in Ian Burn: Minimal–conceptual work 1965–1970 (Perth: Art Gallery of Western Australia, 1992), 70. The note was taken during a meeting with the artist in March or April 1992. Mary Eagle archive.

- ^ The timeline is consistent with Stringer’s (Burn’s ghost-curated) Minimal–conceptual work, the original scene of replication. The issue of replication notwithstanding, the timeline raises new questions. Take for example the dating of Blue reflex 1966–67. The hallmark of these works is the gloss finish achieved with a spray-gun. Yet Burn didn’t purchase this piece of equipment until late 1967 or early 1968, and letters to Melbourne artist Paul Partos in mid-1968 indicate that he still hadn’t mastered the spray gun at that time. Merrilyn Partos archive.

- ^ The press-release incorrectly lists the earliest work in the exhibition as 1966 [not 1965] and the latest as 1993 (not 1994 when Ramsden assembled the final Value added landscapes following Burn's death) correlating with the date-range of the forthcoming Ian Burn: Collected writings 1966–1993, ed. Ann Stephen (Sydney: Power Publications, 2023).

- ^ Ann Stephen, Looking at looking: the art and politics of Ian Burn (Clayton: Melbourne University Publishing, 2006), 120.