Search

You searched for articles ...

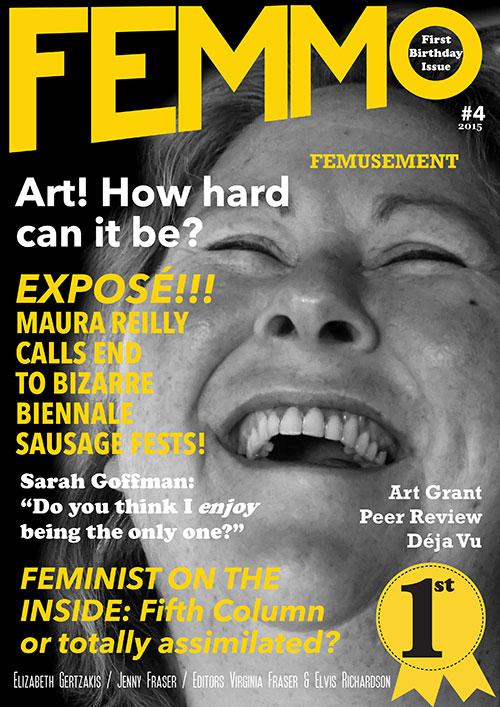

In 2016 the arts in Australia inhabit a dystopian world. It could be described as a place of absurdist contradictions, where only those who have mastered the arcane rules of the Hunger Games have any chance of surviving. Possibly the greatest change is that arts funding is now a partisan political issue in a way that it has not been for some generations. In the past there were concerns about the internal politics of art bureaucracies, but now the allocation of funds to support the arts (or not) has become a party‑political issue. The Commonwealth Government recently presided over the greatest reduction in arts funding in Australian history, but when questioned on this in a public forum, the art‑loving/art-collecting Prime Minister was unaware of the impact of his party’s budgets on the arts. It is probably unfair to blame the current Prime Minister for the devastation that was wrought in the time of his predecessor.

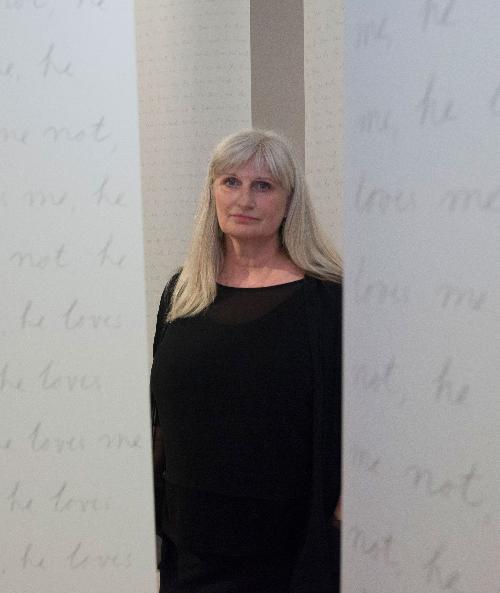

Nearly two decades ago, when artist Rodney Glick and I started discussing the possibility of developing an international contemporary art space in a small country town, people found the idea both comical and intriguing. They laughed when they heard it first but then reconsidered, perceiving a potential beyond the apparent joke. The reason for such hilarity is obvious: contemporary art is so closely associated with the inner city areas that the idea of transplanting it among paddocks and feedlots came across as funny, like a hairy man wearing a tutu.

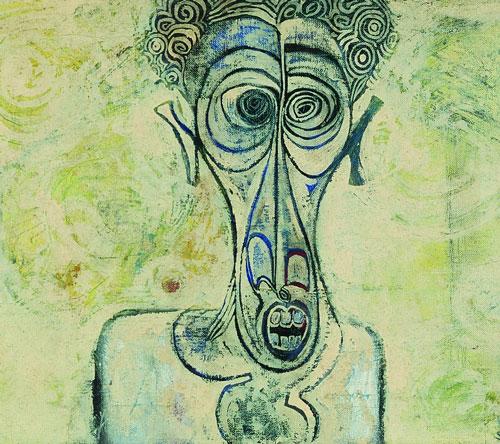

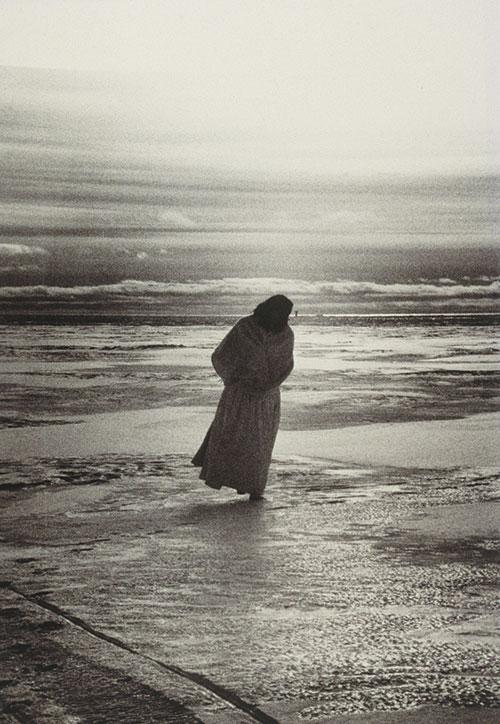

Solastalgia has come to signify distress caused by environmental damage. The term, originally coined by philosopher Glenn Albrecht, specifically addressed the condition of existential distress caused by the physical destruction of one’s immediate environment. As the global extraction industries and the financial institutions that bankroll their reach increasingly dominate, with direct impacts on land, solastalgia is fast becoming a common contemporary condition associated with the loss of ground in our occupation of the planet and a general sense of helplessness.

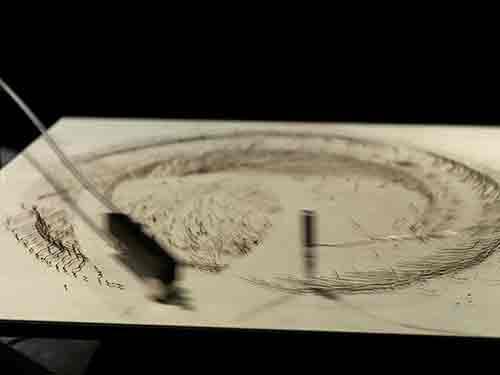

The Palmer Sculpture Biennial is a characteristically transient, remote art event that takes place in the Mount Lofty Ranges of South Australia, some 70 kilometres east of Adelaide. Led by sculptor Greg Johns, who purchased the 163‑hectare property of rain‑shadow country at Palmer in 2001, it has become a place for artistic nomads, who converge on the landscape to create ephemeral and site‑specific art. This unique art event that takes place every two years is aligned with an ongoing program of land regeneration, supported by a community of artists and environmentalists.

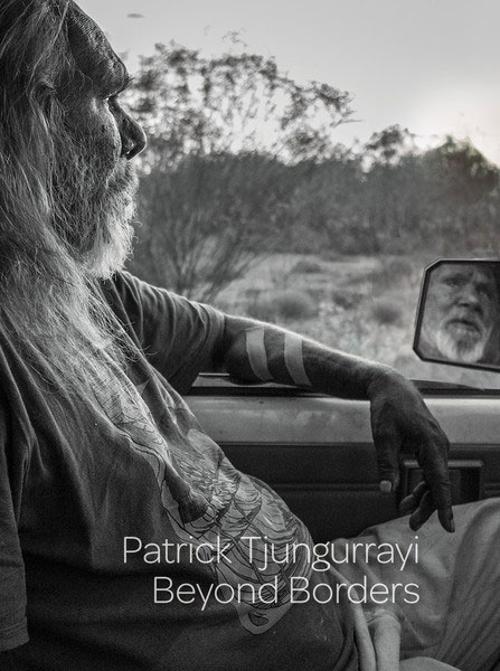

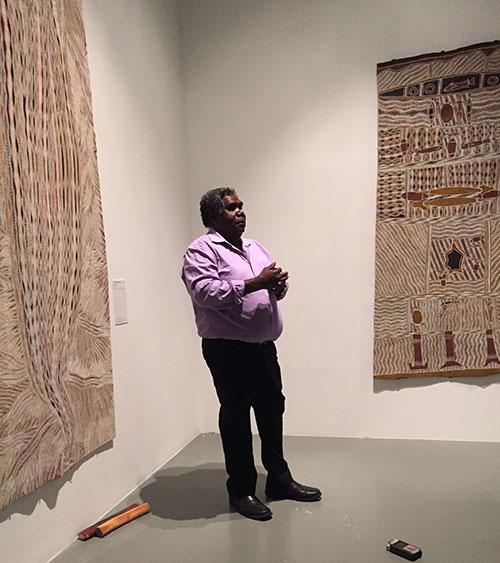

Keynote address presented on 17 April 2015 in Perth as part of the annual Revealed program supporting emerging Aboriginal artists from Western Australia.

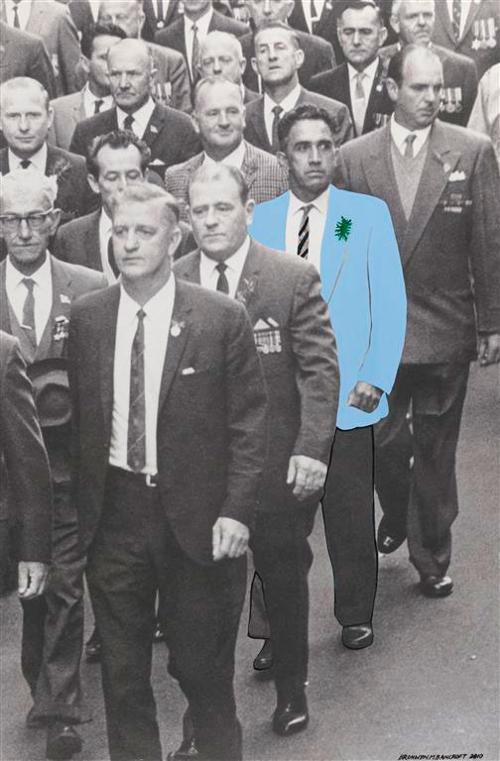

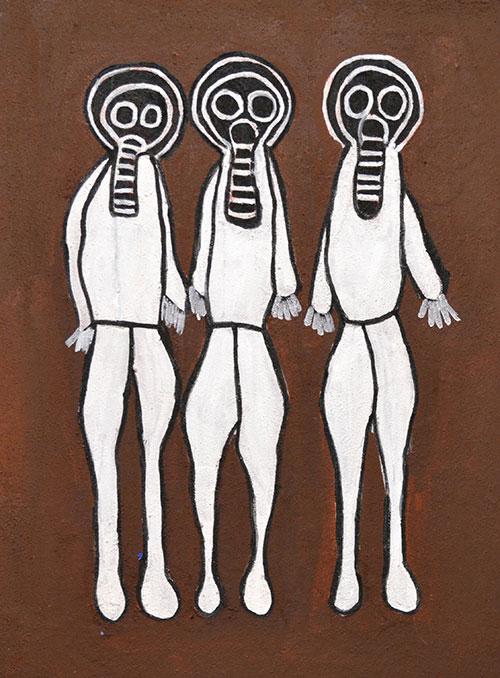

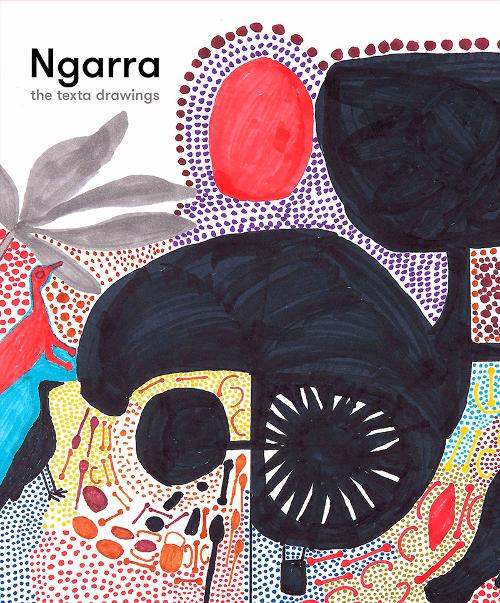

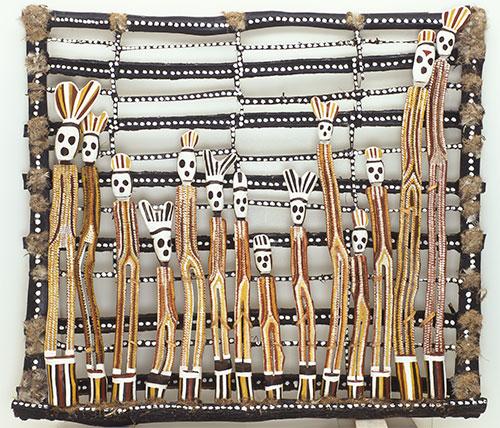

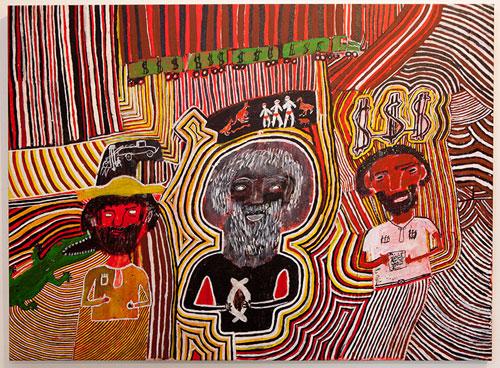

As Indigenous people of this nation we are a sovereign people, standing strong in our culture and remaining true to our heritage. We stand strong in our art; we stand strong in our culture and we stand strong on our country. Our ancestors, communities and families have welcomed many non-Indigenous peoples into this country, and today we see the continuity of our shared culture, history and traditions. I see Aboriginal art and culture at the very forefront of Australian identity and celebrated in such a way that previous generations would not have imagined. Despite these remarkable achievements, we as Aboriginal people in this country have been continually bombarded by waves of dispossession, racism, marginalisation and genocide. I am both angered and frustrated that we continue to sustain the impact of colonisation on a daily basis some 226 years after invasion. We are not recognised as a sovereign people, we continue to be governed by a nation that does not recognise us as equals.

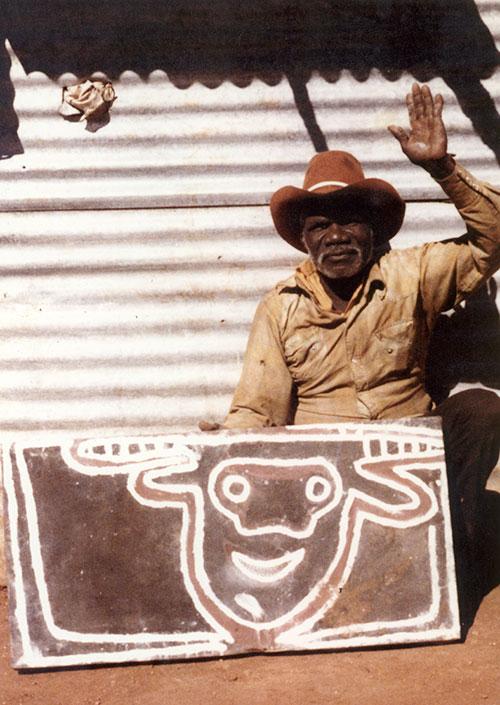

Painting at Warmun has long been linked with the desire of the old people to pass on Gija language to children. At the same time as the Goorirr-goorirr song and dance cycle was given to Rover Thomas by a spirit, Gija elders were requesting that the Ngalangangpum School teach their language. Paintings carried in the dance helped launch the local art movement and the singers and dancers were also the language teachers. They made objects as teaching aids that are now part of the Warmun Community Collection.

Words are like territories. Like invisible boundaries laid down in the vast forest of experience, they parcel up reality into sections which can be named, like addresses or the clan estates of Arnhem Land. To compare two languages can be like overlaying the maps of two different cultures. Just as Manilakarr clan lands, for example, are split between Kakadu National Park and Arnhem Land, the conceptual boundaries of words in two languages rarely align neatly.

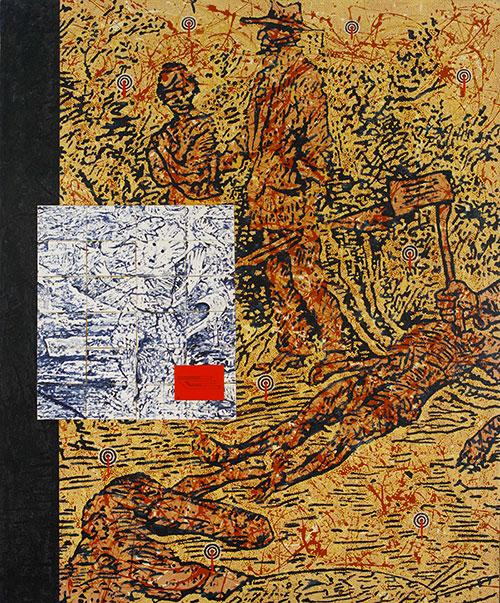

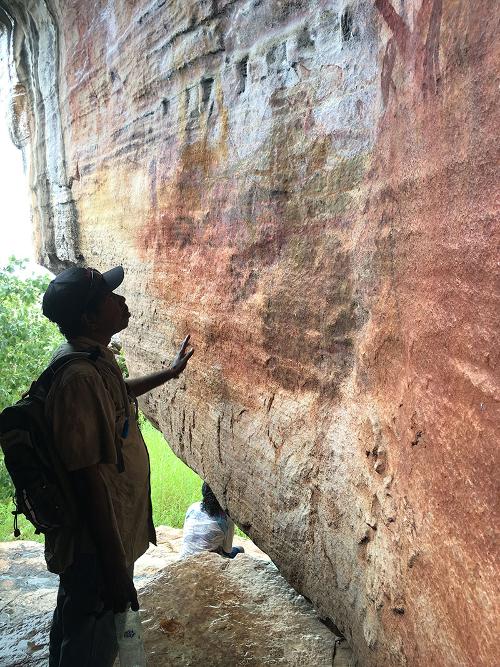

Recent changes to the Western Australian Heritage Act undermine the connection between people and country, placing thousands of rock art galleries at risk. Since the introduction of the cattle industry to the Kimberley region during the early 20th century and the subsequent forced removal of Aboriginal people from their traditional homelands, negative impacts on Aboriginal communities have been well documented. The impact on country, when its people are removed, is equally dire according to Ngarinyin/Nyikina artist, cultural leader and land management professional Rona Charles: “You can’t take people, objects, Junba [song and dance] away from Country and think nothing will happen. Because water, plant, song, animal, people – they all depend on each other. People, for their identity and social wellbeing, and country for ecology.”

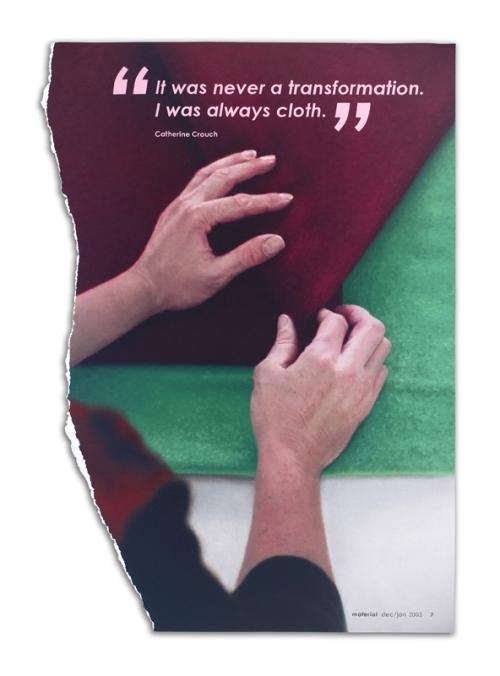

Beginning with batik printing at Ernabella in the APY Lands in the 1940s, hand-printed textiles in Indigenous art centres have become a rich and varied tradition. It has emerged as a significant art form in recent years, particularly for art centres in the Top End.

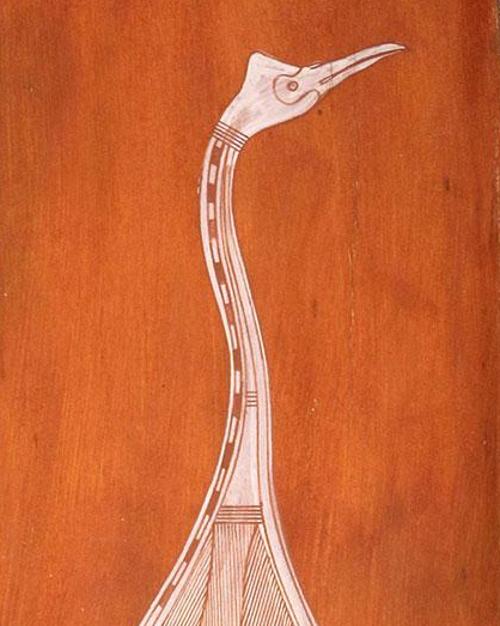

The Tiwi Islands has one of the longest traditions, where the Bima Wear women’s centre has been printing and designing since 1969, alongside Tiwi Design and the Pirlangimpi Women’s Centre. Tiwi textiles are known for their bright colours and bold designs, and are often worn by the local community.

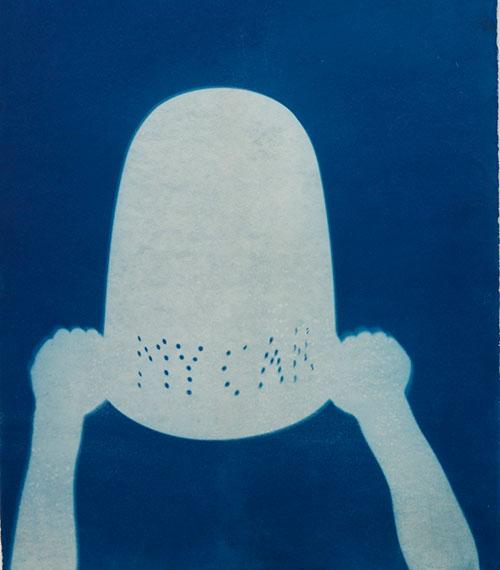

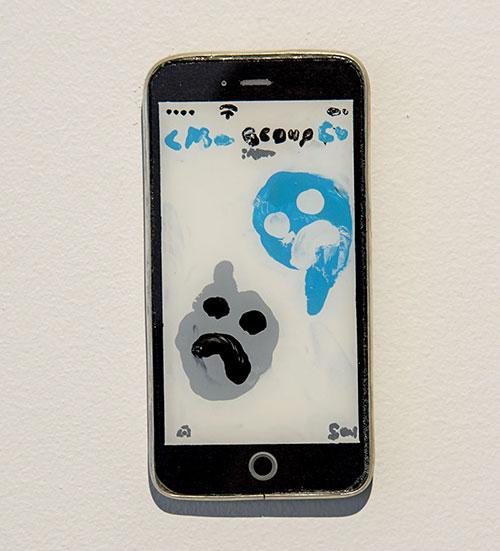

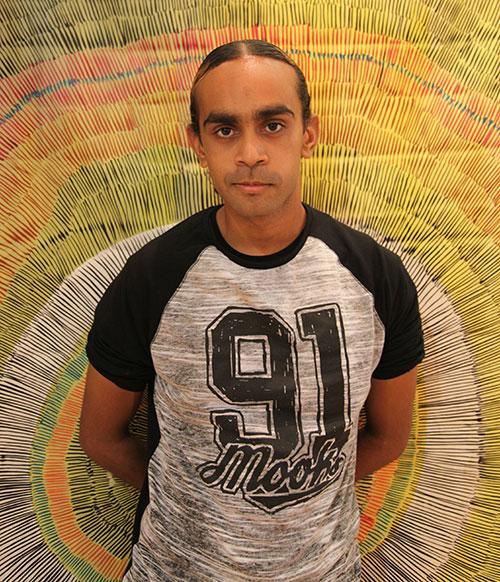

Yolngu people, the traditional Aboriginal owners of North East Arnhem Land, use the word mulka to describe a sacred, but public, ceremony. Mulka also means to protect and share things that are important to us – things that hold our identity, our culture, our connection to country and our past. When our people decided to bring together the films, photographs and audio recordings made in and about our community, the Mulka Project was born.

Yolngu have always had art inside our rumbal (bodies) and our doturrk (hearts). What people make depends on their aims, skill and style. With mobile phones and video cameras we’re making a new kind of Yolngu art. But it still comes from inside. It still comes from Yolngu doturrk.

Under the guardians of the mission, Cornelia Tipuamantumirri grew up on Bathurst Island in the Tiwi Islands. She went to school under the old mission church and was given a slate and chalk. Salvation came in the form of the Catholic nuns. She lived in a dormitory with the other Tiwi girls. She was never allowed to speak her language or practice our culture.

I am a Garawa man. My country is in the southwest Gulf of Carpentaria. When I was young there was no whitefella schooling for us Aboriginal kids. My school was the bridle and the blanket, learning on the pastoral stations where my father worked. Our future was set as labourers on whitefella stations. This is the reason I don’t read and write. I’m not ashamed of this.

I was taught our law by my grandfathers, father, uncles and other senior kin from the southwest Gulf peoples: the Mara, Gudanji, Yanyuwa and Garawa. Knowledge came to me through ceremonies, hunting, fishing, gathering and travelling through our country with the old people. We sing the country.

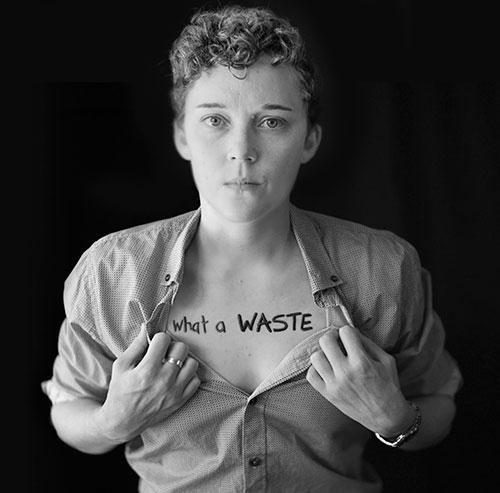

This series explores living conditions in our community of Borroloola in the Gulf of Carpentaria, Northern Territory. I am a Yanyuwa/Garrwa woman. I call it “My country, no home” because we have a Country but no home, people are living in tin shacks, in matchbox-sized houses. Even traditional owners here don’t own houses. I wanted to take these photos to show the world how my people are living. The project is not to shame them.