Search

You searched for articles ...

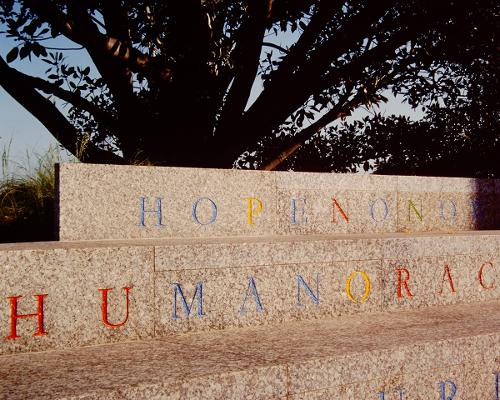

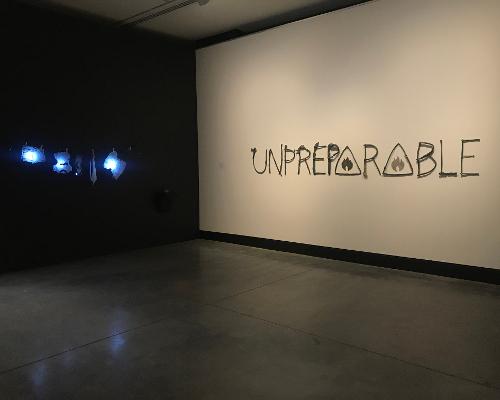

In a sparse gallery space, a detached hydraulic door closer lies splayed on a white panel. This unassuming readymade by Belgian artist Steve Van den Bosch provides a subtle topographical deviation on the dull cement floor. Titled Assistant (2021), the closer was relocated from the gallery director’s office for the duration of Round About or Inside (30 September 2021 – 20 November 2021) at Griffith University Art Museum, Brisbane. Appropriately placed on the ground—the anti-art/anti-functional gesture par excellence—the artwork suffices as a miniature monument to technologies of access, reflecting on how we move through spaces and what mechanisms exist to ensure our safe and comfortable journey, to welcome us, or to deny us entry.

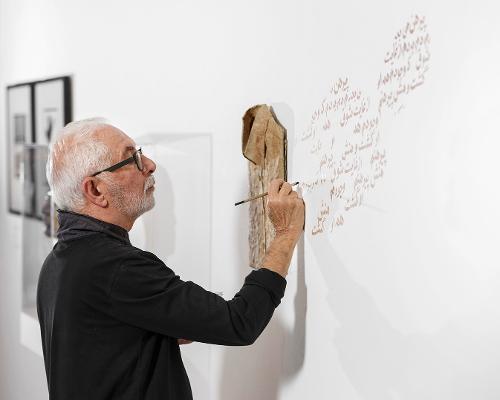

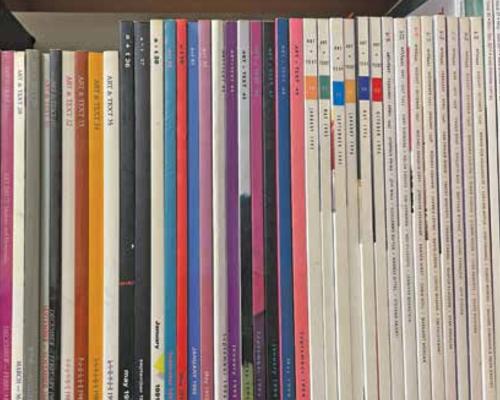

Founded in Melbourne by Paul Taylor in 1981, the Australian art magazine Art & Text began the same year Stephanie Britton founded Artlink in Adelaide. During the 1980s and 1990s, Art & Text made global waves. From its earliest issues, it infused art criticism with critical theory when that very notion was radical and fresh in Australia. By his mid-twenties, Taylor had curated POPISM at the National Gallery of Victoria (1982), edited the landmark volume Anything Goes: Art in Australia 1970–1980 (1984) and had moved to New York to become a renowned critic for Vanity Fair, Flash Art and The New York Times.

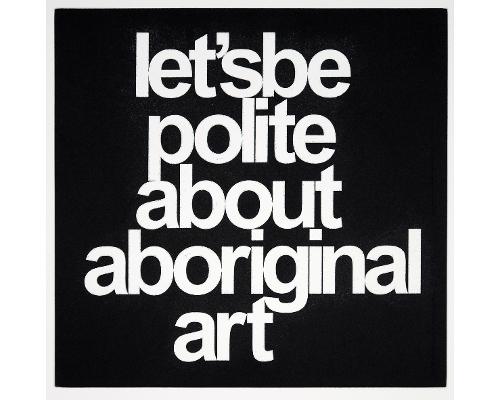

In an essay discussing art criticism and the pain it can inflict, the European critic Jan Verwoert reflects on the way most writing on contemporary art has sublimated its brutality or—some would say—its honesty: The main reason for the polite tone in art criticism [...] is that—contrary to the distance that, for instance, separates the opera critic from the social milieu of the orchestra musician—art critics and artists mingle in the same milieu. There is no stage between them. It’s impossible to deny that you are part of the same living social community when the artist you just wrote badly about is also someone you are bound to soon run into again at the next opening in town ...

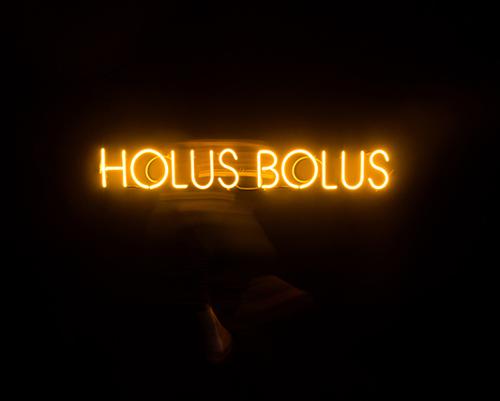

Ngami-lda-nha / looking

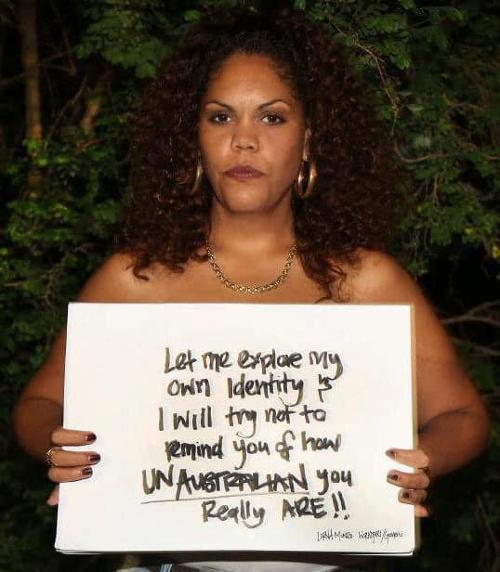

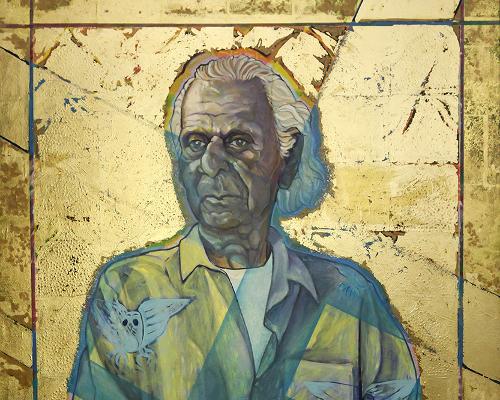

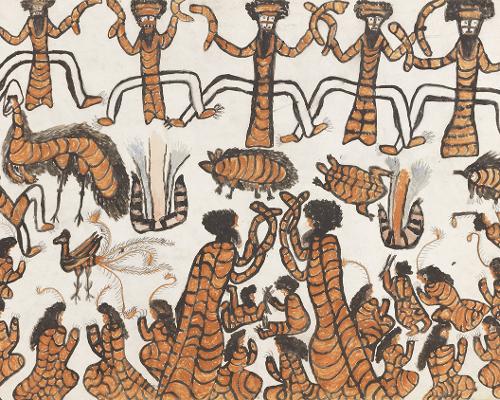

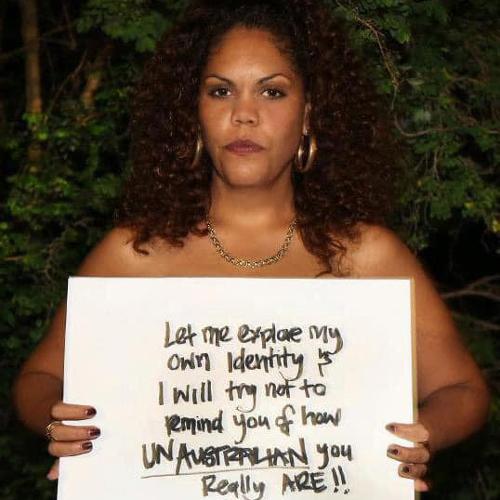

In our past/present/future continuum, we can look simultaneously to the potential of what is and what can be, acknowledging that what we are currently seeing and experiencing is also that which is ‘not yet’. Friend and fellow Gamilaroi Countryman Joshua Waters speaks to the sight/foresight of our ancestors through a story of Garruu Winangali Gii/Uncle Paul Spearim, pointing out to him a barran/boomerang in a tree. Joshua recounts how he spent minutes ‘foolishly looking …for a literal boomerang’, only to realise later that what Garruu was talking about was the ‘future potential state’ of a particular branch that had the perfect curvature from which to shape a barran. Looking to the future, in the now, we also acknowledge and deeply winangali/listen/understand/respect the past work and words of other Blak artists, authors, and thinkers who have generously shaped and progressed what is—in terms of Indigenous art and art criticism, our ongoing agitation for autonomy, agency, and the re-centring and de-homogenising of our art practices amidst constant mainstreaming pressures and perspectives.

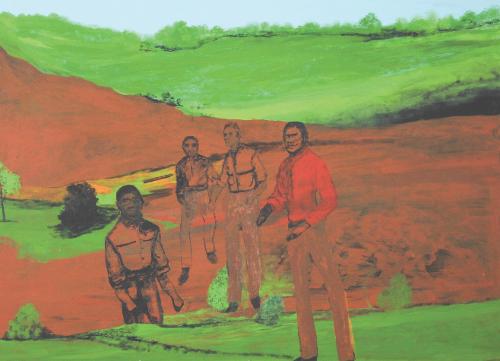

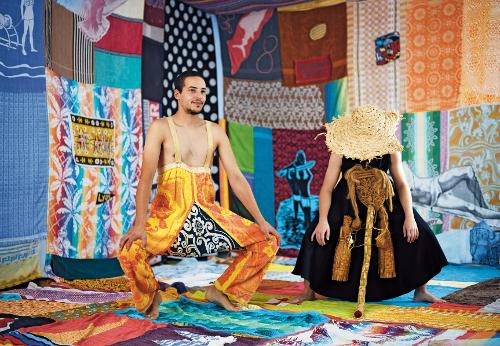

Because their guiding principles aligned, D Harding was a natural fit as the candidate for curating an exhibition of Australian Aboriginal art from the Luciano Benetton and Imago Mundi Collection. Referring to their Bidjara philosophy, D wrote in their proposal: ‘We don’t exclude anyone; we allow people to exclude themselves.’ They met at the confluence of a similar ethos and aesthetics that underpins D’s art practice and Benetton’s projects, including his well-known fashion house United Colors of Benetton.

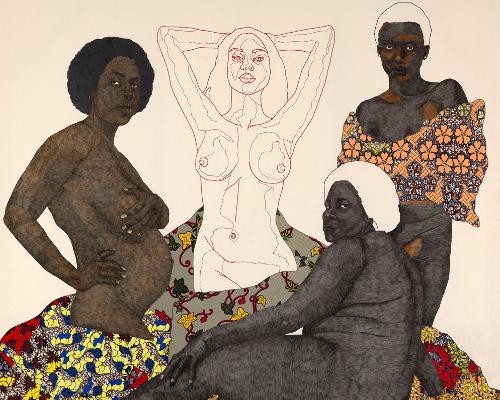

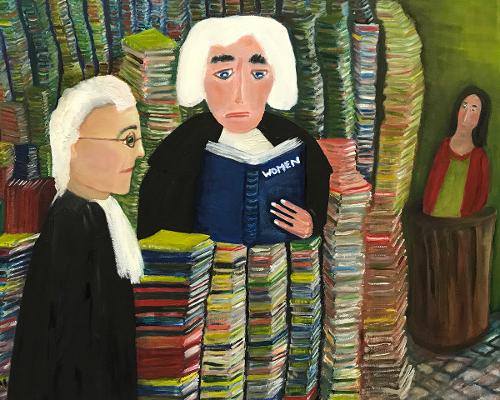

My formal arts education began in a strange place: the Elisabeth Murdoch building at the University of Melbourne where I took an art history elective. Built in 1885 by Joseph Reed, the Gothic architecture reinforced the rigid authority of the colony. Glaringly elitist, it resembled both church and orphanage. It was full of confusing hallways, which remained impossible to navigate. Inside its constructed edifice, middle-aged white men in paisley shirts lectured, with exotic hand gestures, on First Nation artists (when they were spoken of at all). And white women in the faculty asserted a self-righteous paternalism that was far worse.

I paint my face as my mother’s mothers have done before me

In this new ritual sitting on my bedroom floor

We name each pigment after revolutionaries

Because I am my mother’s daughter

‘How did it begin?’

‘Desire. Sex. Lesbianism.’

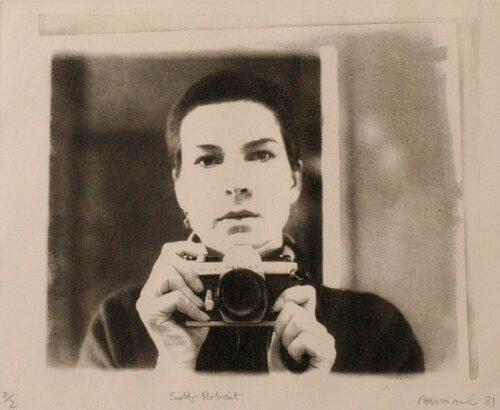

In 1978, Helen Grace visited Amazon Acres, a women’s commune in the mid-north coast hinterland near Wauchope, NSW. She packed her new Olympus camera and brought home several rolls of film. Returning two years in a row, Grace unintentionally collated an archive of one of Australia’s most audacious experiments in utopian living. There are eleven proofsheets: hundreds of photos in all, mostly black and white. For Friendship as a Way of Life (2020), curated by José Da Silva and Kelly Doley at UNSW Galleries, Grace edited these photos down with the assistance of Da Silva to twelve images for a series entitled And awe was all that we could feel.

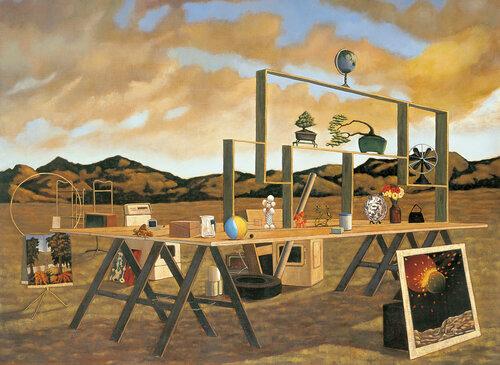

Group exhibitions are ideological texts which make private intentions public.

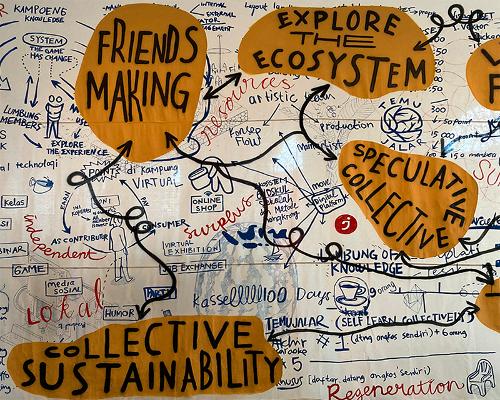

In May 2021 the Turner Art Prize announced five artist collectives as their nominees. It was the first time the premier British internationally recognised award did not include an individual artist, reflecting a changing landscape. The prize’s intention is to ‘capture the mood and moment’ of contemporary visual art, and with this year’s nominees, Tate Britain make a bold public statement to the collectivisation of artistic practice. However soon after the announcement, nominee Black Obsidian Sound System released a statement on Instagram criticising the institution:

Although we believe collective organising is at the heart of transformation, it is evident that arts institutions, whilst enamoured by collective and social practices, are not properly equipped or resourced to deal with the realities that shape our lives and work.

“Look at that: you made it”

Alanna Okun, The Curse of the Boyfriend Sweater.

I learned to sew as a young child. Sitting in my mother’s lap, I picked up the delicate and confident touch and precision to snip threads and manipulate cloth as she made clothes for herself, my sister and me. Before I could read and write, I was adept at using a needle and thread to form my creative visions in the three-dimensional materiality of cloth. Mum taught me to cut, alter and mend to make efficient use of materials and garments, a make-do-and-mend sensibility that she learned from her own mother, raised during the Depression in rural South Australia. At my mother’s side, I also came to understand and express my sartorial sensibility and identity through the garments I made. Mine is a common story.

“Beauty is a curse and I’ve got it.”

Effie is the most beloved character from the 1989 Australian TV sitcom Acropolis Now, which is set in a fictional café of the same name. Her character is a defiant assertion of “wog” ways: her high hair and incessant gum-chewing are flamboyant stereotypes, but her character, and those of her castmates, were then new to Australian TV. Acropolis Now, a spin-off from the highly successful stage play Wogs out of Work, dislodged the Anglo-centric narratives of Australian comedy TV. The show has been credited with popularising the term “skippy” or “skip”, used by Greek, Italian and other non-Anglo Australians to refer to Anglo-Celtic Australians since the 1970s.

How do you haunt a ghost?

For the most part, this is not a rhetorical question because, simply put, a ghost can’t be haunted: it is the medium of haunting itself. The space-time paradigm of the terrestrial won’t allow for it. Haunting, as conceived in the vernacular imagination, demarcates an activity reserved solely for “the unhallowed dead of the modern project”, those improperly buried inheritors and victims of repressed, unresolved violence and injury—those whose lives were stalled and silenced. So by virtue of this logical impasse, you can’t technically haunt a ghost.