Search

You searched for articles ...

[I]t is increasingly clear that there are no topics or phenomena to which a feminist analysis is not relevant—at which point it is useful to consider feminist theory ... as a set of techniques, rather than as a fixed set of positions or models.

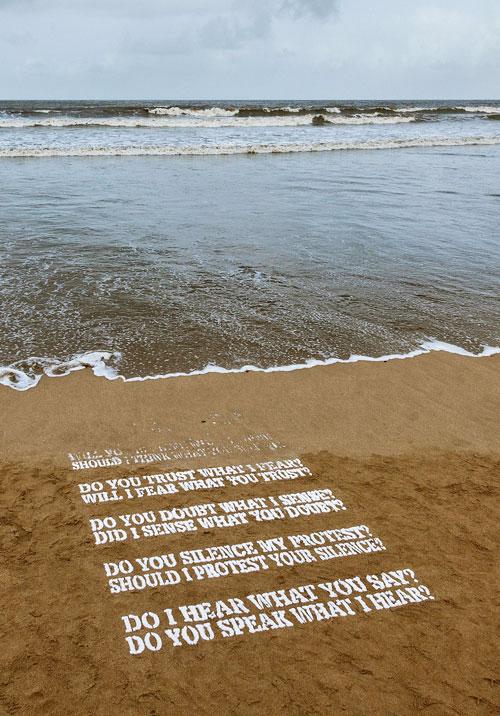

The state of the art world and of feminism in the twenty-first century ushers in different ways of doing political activism, cultural work and theory. The intergenerational aspects of feminism and how this has been enacted in the visual arts in recent years represents a refreshing change from earlier perceptions of waves of feminist theory that tended to privilege the new. The visual metaphor of the new wave dashing the old against the shore appears to replicate traditional paradigms in what some have called either an Electra or an Oedipal contestation where the new generation kills the old feminist mother in order to please the father (the academy).

I have lifted the title for this essay from Narratives of Dis‑ease (1990), a series of works by the late British photographer Jo Spence. The series was made following the artist’s partial mastectomy for the treatment of breast cancer. Closely‑cropped around her body, the photographs show Spence partially nude, using props and performing emotive gestures, compositions and sight gags that were suggestive of the sub‑titles she ascribed to each individual image: Expunged, Exiled, Included, Excised and Expected.

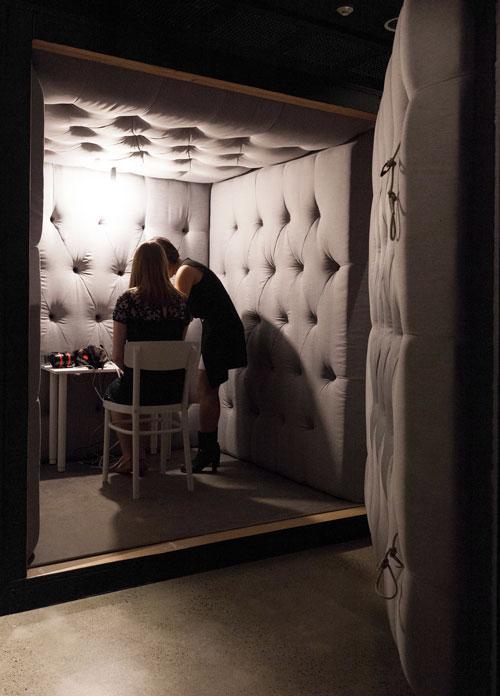

Why I do them is to be around people that don’t have any fear.

I want to see what it’s like to be around people who are really happy.

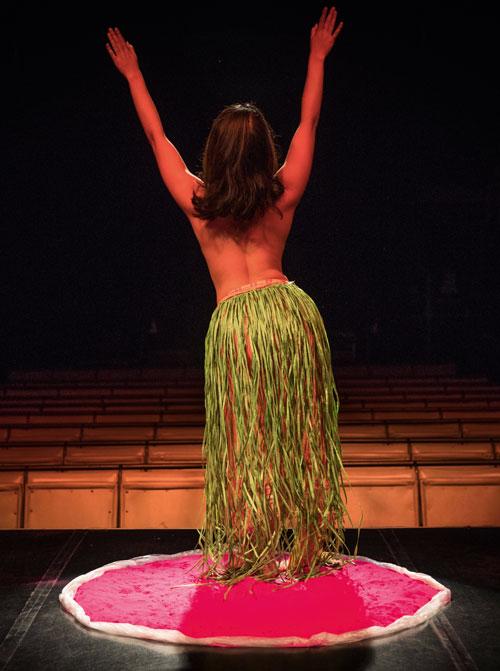

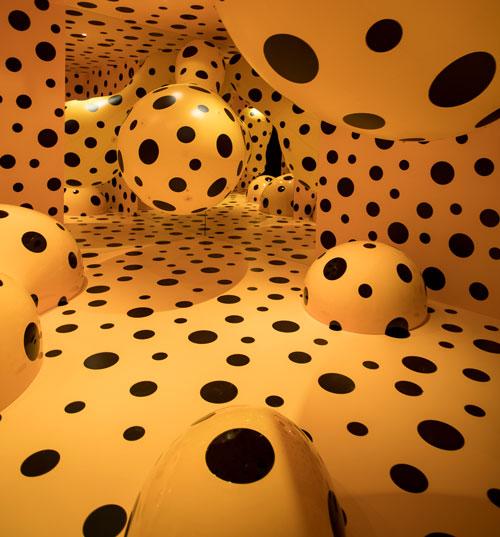

Stuart Ringholt’s anti‑anxiety Anger Workshops and stress‑healing Naturist Tours step outside the usual model of clinical healing practices. They revisit the potential of being happy by living in the moment as a form of liberation and group therapy that is creatively driven. The first of the Naturist Tours began as part of a show on art and therapy named Let The Healing Begin (2011) at the IMA in Brisbane. Curator Robert Leonard commented that many regular gallery goers politely declined the invitation to take part, and although he was low key in his advertisement of this aspect of the show, it created a tremendous amount of community and media interest. Fast forward to the subsequent tours through the Wim Delvoye Retrospective at MONA (2011), and James Turrell: A Retrospective at the National Gallery of Australia, and Ringholt’s practice has all but surrendered to the demand, with an accelerated following.

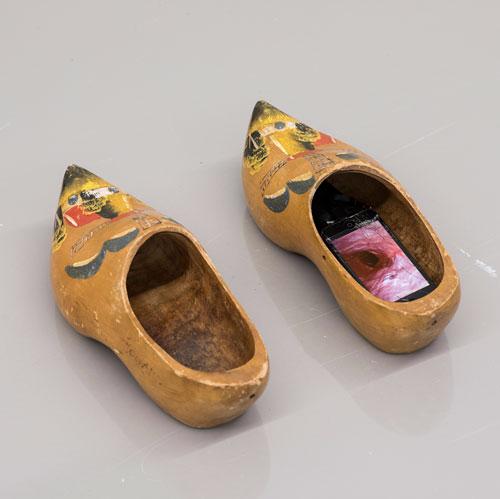

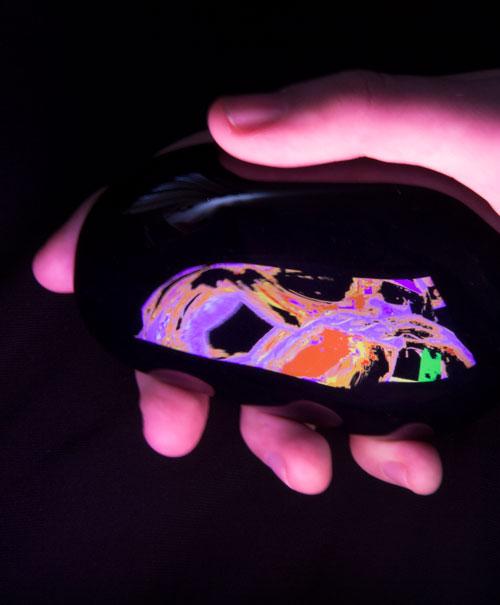

The affective power of a photograph is perhaps never more potent than when the subject is a lost loved one, as Roland Barthes famously discussed on contemplating a portrait of his dead mother. This appreciation of the role of photography is harnessed in a new digital artwork by the Miyarrka Media collective which uses family photographs, including many images of deceased family members, as the basis for an interactive digital artwork about the importance of family and feeling in an age of interconnection.

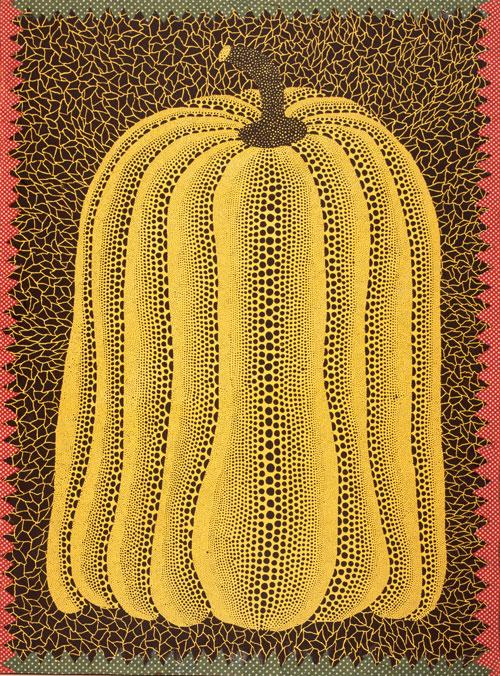

I am autistic. I perceive and experience the world through sensory and cognitive pathways unique to autism. Neuroscience documents this as “sensory atypicality” and “detail‑focused perception.” In terms of lived‑experience, this means the senses react in ways different from the norm, and the mind attends to minutiae that most others dismiss or miss altogether. Autistic sensory‑cognitive idiosyncrasy unpacks in myriad ways, varying from person to person and in modulations that range from intense attraction to extreme aversion.

I am in France. I have been working towards a presentation related to my research on panic at the Sorbonne, at a conference called Lire Pour Faire. I am anxious, sick with it, actually. My paper is dry and I need wet. The wet of tears, the wet of biochemicals pumping through blood, the wet of fear-piss. I want to vomit and I want to scream. Instead I sit in my room and hyperventilate. I find my friend and disclose my fears to her. I am in a state. She convinces me to do a practice presentation for a group of people who will be kind and supportive. I perform my disquiet and my insecurity and it is painful, and the pain is felt, and there is silence. There is a sitting back, a sinking down, a closing of laptop lids. There is quiet. Sometime after the quiet somebody tells a story and there is talk, feedback, questioning, exchange, confusion. This is where the research happens. Elsewhere, and otherwise, and afterwards.

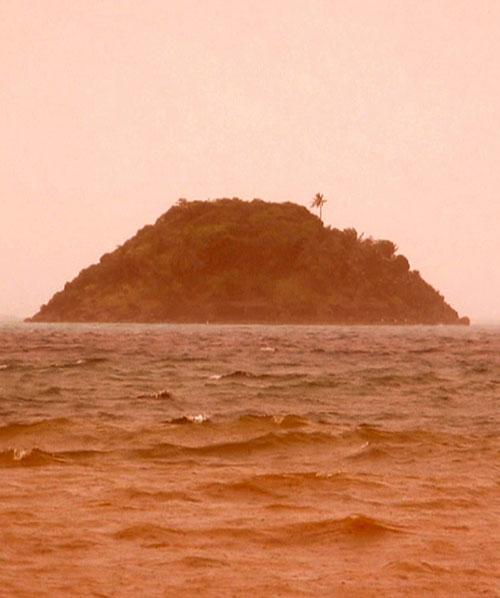

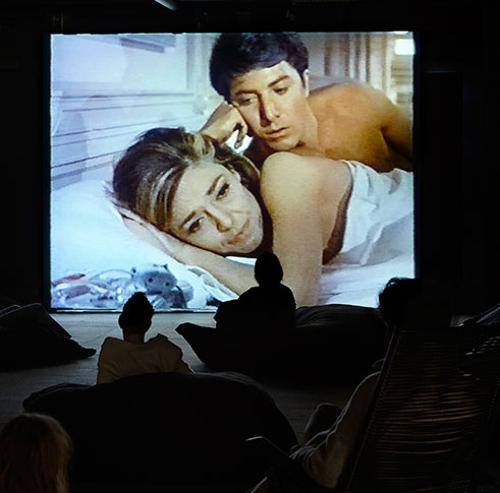

One of Tracey Moffatt’s lasting cinematographic memories, as she told me, is of films with harbour scenes, of working ports, rough workmen, the coming and going of exotic people, fogs, and foghorns. Tracey Moffatt’s photographic and film work commissioned for the Australian Pavilion in Venice responds to this landscape of cinematic time.

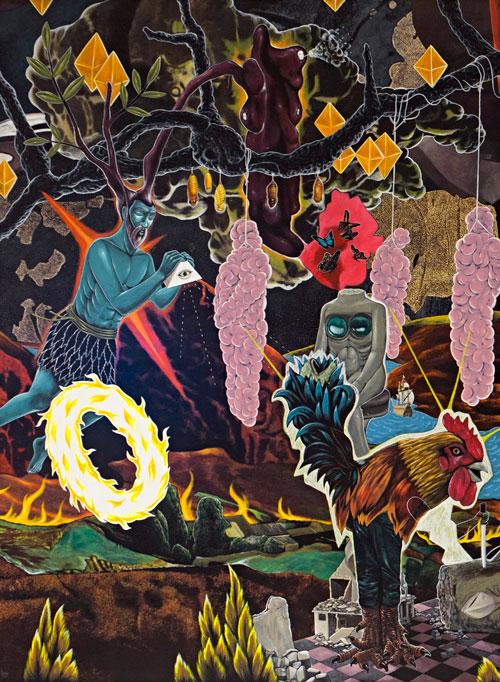

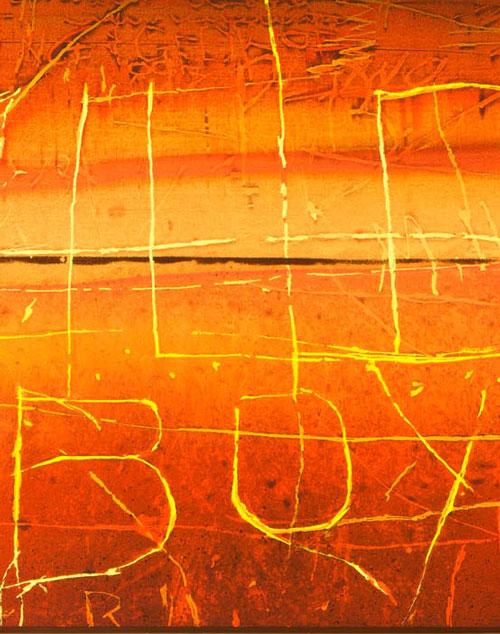

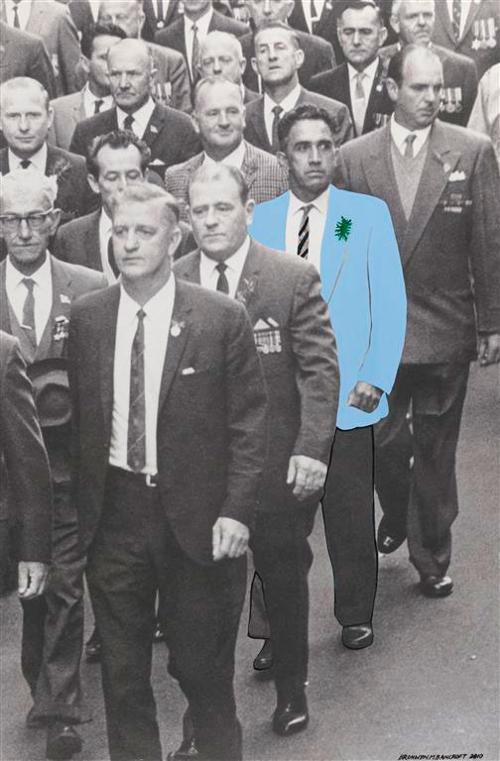

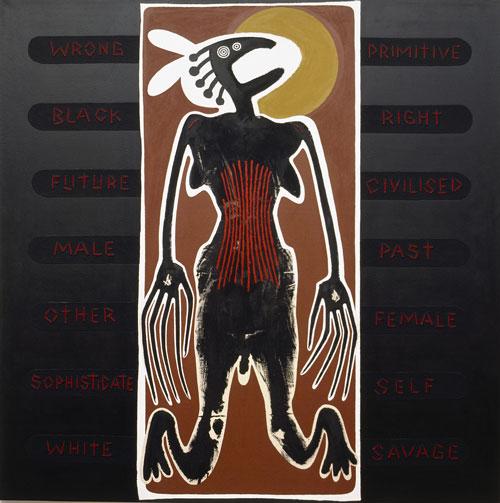

Black is the New White is Nakkiah Lui’s romantic comedy commissioned by the Sydney Theatre Company for the May/June 2017 season. It milks laughs from a stereotypical narrative of a privileged young black woman bringing her inappropriate boyfriend home to meet her parents. The twist—although not much of one these days—is that the boyfriend is white. Black is the New White is also the name of the 2007 autobiography by African American comic genius Paul Mooney. We can reach further back to the early 1990s: to Gordon Bennett’s sweet watercolours of black angels and his more ghoulish messenger between worlds, the large scarified Altered Body Print (Shadow Figure Howling at the Moon) (1994) with its mashed binaries and grotesque white/black, male/female, human/animal totemic‑like monster. Before Bennett there was Tracey Moffatt’s sweet black angel Jimmy Little on the royal telephone to heaven, an ironic serenade to her grim horror film, Night Cries (1989), which unsettled normative understandings of black/white relations with chilling effect.

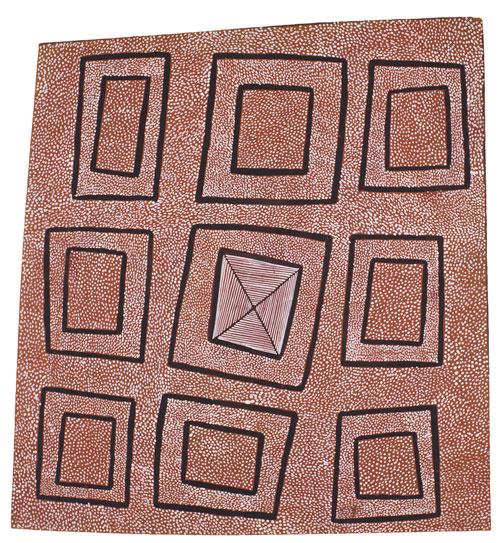

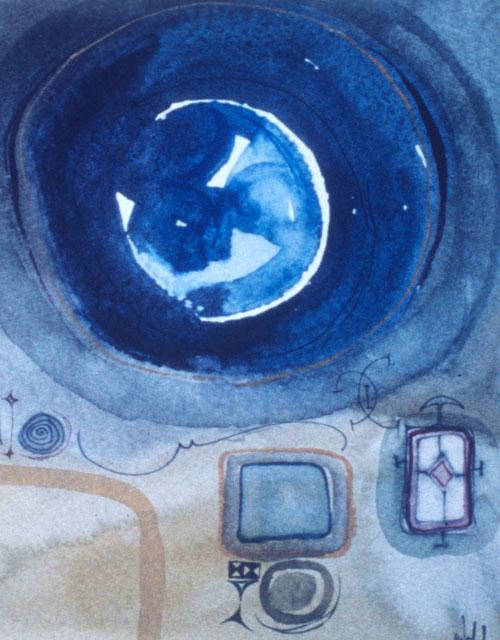

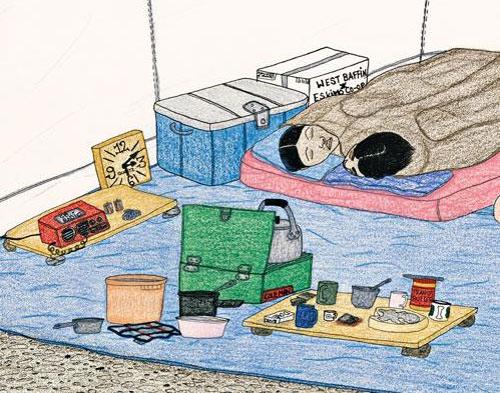

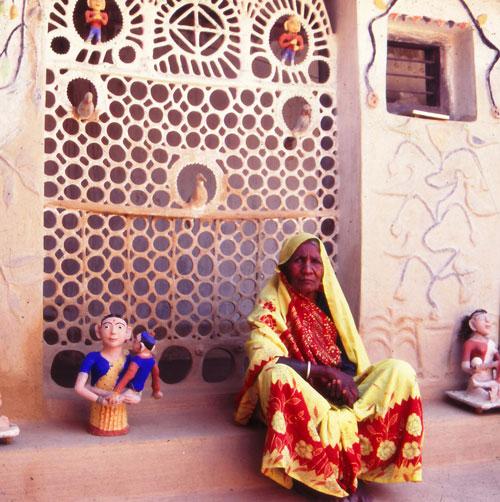

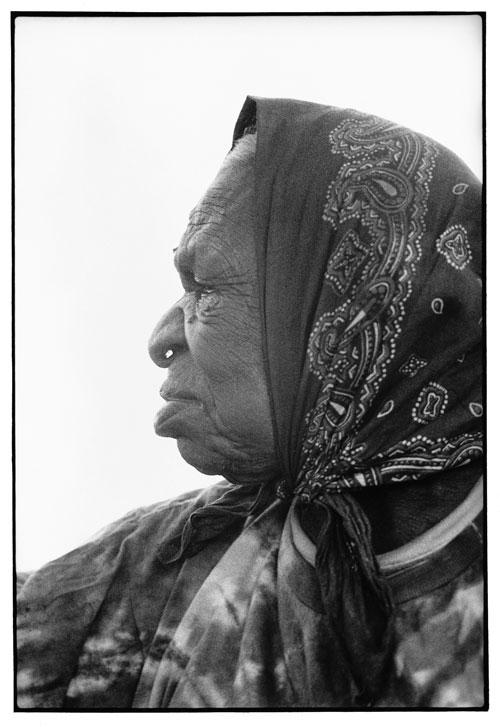

Art critic Robert Hughes made the assessment that Aboriginal art was the last great art movement of the twentieth century. It started at the Aboriginal community called Papunya, in which Aboriginal men had been painting on canvas for the outside market with great success since the 1980s. The Papunya art style, as it became known, sometimes compared to forms of Western modernism—from abstract expressionism to minimalism and even conceptual art—presented a comparison that was rarely taken literally, although some critics of the 1987 Dreamings exhibition in New York did wonder if the Aboriginal artists had been appropriating New York art. But when it came to the late paintings of Emily Kame Kngwarreye, critics really did start to question the relationship between modernism and Western Desert painting, ascribing to her the genius and expressive freedom associated with the masters of Western modernism.

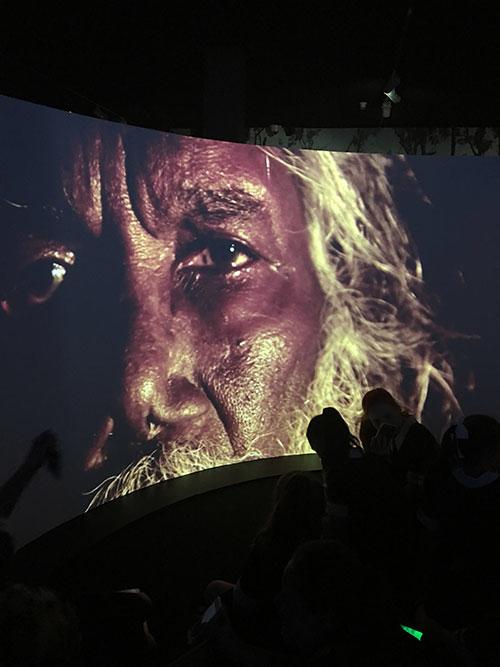

On the cross‑cultural collaborations of filmmaker Lynette Wallworth working with Nyarri Nyarri Morgan and Curtis Taylor

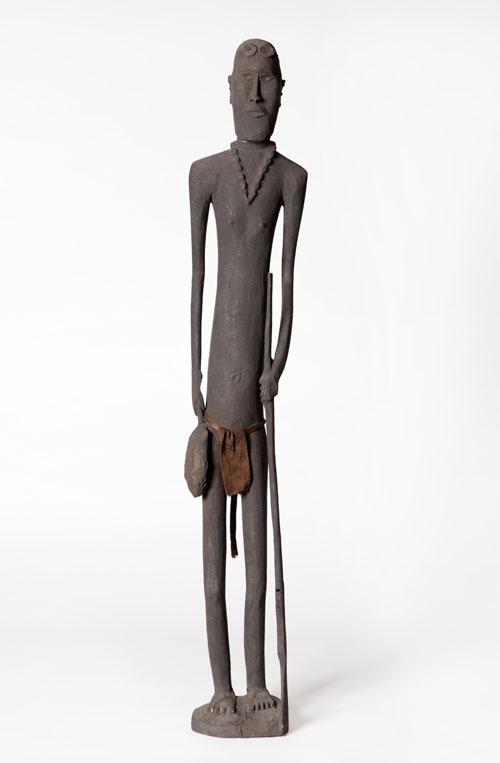

An emerging history of transcultural engagements in recent years is evident in the growing number of projects by Australian Indigenous artists working with collections held by British cultural institutions. From Judy Watson’s research at the British, Horniman and Science museums in the 1990s, to Daniel Boyd’s residency with the Natural History Museum and projects by Brook Andrew and Julie Gough at the Cambridge Museum of Archeology and Anthropology, these Australian Indigenous artists have negotiated complex histories of colonial collecting practices, contemporary modes of museum display, issues of cultural ownership and repatriation, as well as the role of the artist as a new kind of researcher and interpreter of archives and cultural heritage.

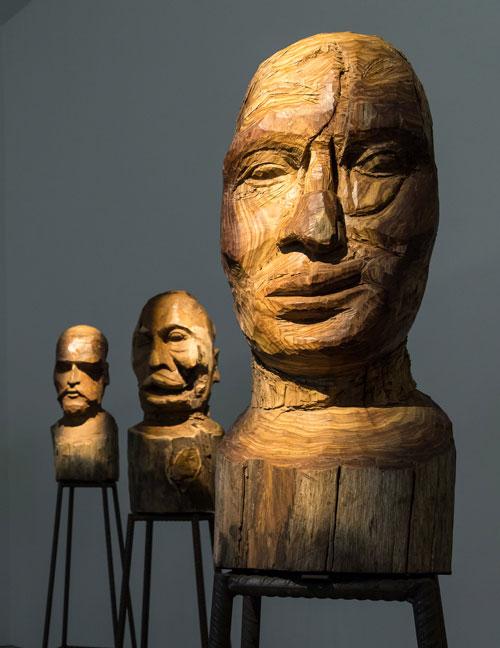

I can remember the first time I was taken into a museum storeroom. I remember it being still, organised, open and unashamed. I could see countless rows of shelving stretching from the floor to a ceiling so high that the optical illusion it created masked its vastness. The air was unmoving, the smell musty and organic. When my eyes adjusted to what lay on these shelves I had trouble taking it all in: wood, feathers, stone, bark, ochre worked in countless combinations. I searched for the clues which would guide me to material from north‑western New South Wales, to my Father’s country, and my ngurrambaa (Yuwaalaraay) or “family land”.