Search

You searched for contributors, issues and articles tagged with Socal Justice ...

Contributors

Issues

Articles

When I was eleven, I assumed the role of keeper of the family archives: with both parents working and me the younger sibling, I probably had the most time on my hands. But I also felt a strong compulsion to guard mementos from family holidays and special occasions, including images. With the solid moral universe of a child that age, I wanted to capture the “true” version of events, preferring candid to posed photographs. I was renowned for gonzoing formal photo opps by pulling a face or kicking out an inopportune leg. You can imagine my outrage when I discovered my carefully compiled albums had been raided. Every “unflattering” photo of my mother had been removed, leaving virtually no trace of her. When confronted, my mother was unrepentant and refused to return the photos, claiming she had destroyed them as was her right. I was so angry that she would presume to interfere in our collective family record and incensed at what I saw as her hypocrisy and inability to face “the truth”—that she was ageing. Looking back, I have a great deal more compassion for my mother’s response. But this poignant memory makes me reflect: how many other family archives suffered a similar fate (let alone in the digital era)? Was internalised shame at work? And, what counter‑truth was my mother asserting?

I submit to my stocktake shifts, become their restless subject, sighting, countersigning, pitting numbers and images against objects. “Randomised”, my colleague tells me, from an appropriate social distance. A performance of witnessing without expectation (at least on my part) which is why his appearance was closer to a manifestation.

Stephen Benwell’s little statue. With a rush of feeling, he wholly punctured my procedural glumness. His tender realness, eyes fluttering upward to a neighbouring stoneware pot, he chastises the unimaginatively robust seventies ceramic for what it might have been. His twenty-something centimetres of tragicomic beauty resolute against the silent grey of our diligence. Not just present but a presence of self-elegiac composure. A resistance.

We do not see like a camera. A camera registers everything reflecting light into its lens, but human perception is selective. It is an economy of resources that has evolved over millions of years so that now, neuroscientists tell us, only about twenty per cent of what we perceive visually from moment to moment is actually passing through our eyes. The rest is constructed from memory and expectation. Our experience of the world is a product of interactions between abstract top-down visual memory templates and bottom-up sensory ones. Since the former is subjective, we rarely perceive those things that we fail to consider. Sometimes, to understand the bigger picture, we must squint our eyes and soften our focus; to concentrate less on the things we seek and become conscious of the interplay in how things blend together.

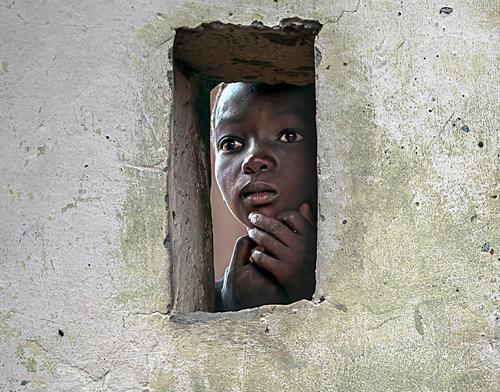

Tracey Moffatt’s series Body Remembers (2017) draws its title and responds to the poem by Constantine P. Cavafy (1918). In each of the series of large photographs we see a woman alone, in the ruins of colonial buildings, on the shadows of eroded stones. We see her looking out of windows, looking out into the distance. As the viewer, we see the back of the woman’s head, or the shadow of the woman, or her face that is covered by her hands as the Aboriginal woman maidservant looking out. The body in this title could be read as both our country and our flesh. The sovereign woman mourns. What do we mourn?