Bernard Smith's assertion in 1943, that it is "truly absurd nowadays to talk of 'modern art' as a single entity,"[1] encapsulates a sentiment that has persisted through the decades and finds resonance in Margot Osborne's exploration of Adelaide's art scene. Osborne's work, a solidly researched and expansive history, with re-printed archival material and an extensive index forming a doorstop omnibus which chronicles the critical historical events and figures who have shaped Adelaide and South Australian art.

Through a series of overview chapters by Osborne and commissioned essays by a range of experts and veterans of the local scene, (alongside anecdotes from cultural commentators including poet and publisher Max Harris, critic Robert Hughes and Stephanie Britton, founding Editor of Artlink), Osborne's encyclopedic compilation of essays illuminate what she argues is the uniqueness of Adelaide's artistic landscape between 1939 and 2000, while situating it within broader cultural and socio-political contexts of Australian and international art.

The introductory chapters set the stage, delving into Adelaide's colonial past and its evolution into a provincial capital with a distinct identity. Implicit in this historical backdrop is the tension between pride in provincial status and a desire for cultural independence from the rest of Australia. Osborne highlights the enduring influence of conservative conceits imported from the British Empire, which persisted in government and cultural institutions until the 1960s. However, she also acknowledges moments of rejuvenation and change, particularly under Don Dunstan’s state premiership (1970–79), which heralded a period of social and institutional transformation. Central to Osborne's thesis is the notion that a master narrative of Australian modernism must include regional diversity to avoid oversimplification. She argues that Adelaide's art scene, with its distinctive blend of influences and perspectives, contributes to the complex tapestry of Australian art history and its contemporary art today.

Tracing the trajectory of Adelaide's art scene from the mid-twentieth century to the start of the new millennia, the text highlights key figures, movements, institutions and exhibitions that have shaped its evolution. One of the recurring themes throughout is the tension between traditionalism and innovation, exemplified by the struggle to define terms like "modern" and "contemporary" art. Osborne challenges narrow definitions of avant-garde practice, advocating for a more inclusive or pluralist approach that embraces a broad spectrum of progressive art forms. The book takes a critical stance toward labels like "parochial" and "provincial mediocrity," which Osborne argues perpetuate stereotypes about local artists' inferiority. She emphasises the need to challenge these perceptions and to celebrate Adelaide's cultural achievements in all their diversity.

The book's collaborators’ exploration of Indigenous art and its shifting place within the Australian canon is particularly insightful, and includes the significant strides made in recognising Indigenous art as central to the Australian cultural landscape, from the periphery to the forefront of contemporary art discourse. Catherine Speck, Doreen Mellor and Nici Cumpston collaborate on the chapter “First Nations Art: the move to centre stage” and Philip Jones' “Aboriginal art and shifting paradigms” offers an examination of the changing patterns of collecting and exhibiting Indigenous art, highlighting the contributions of the South Australian Museum and the Art Gallery of South Australia.

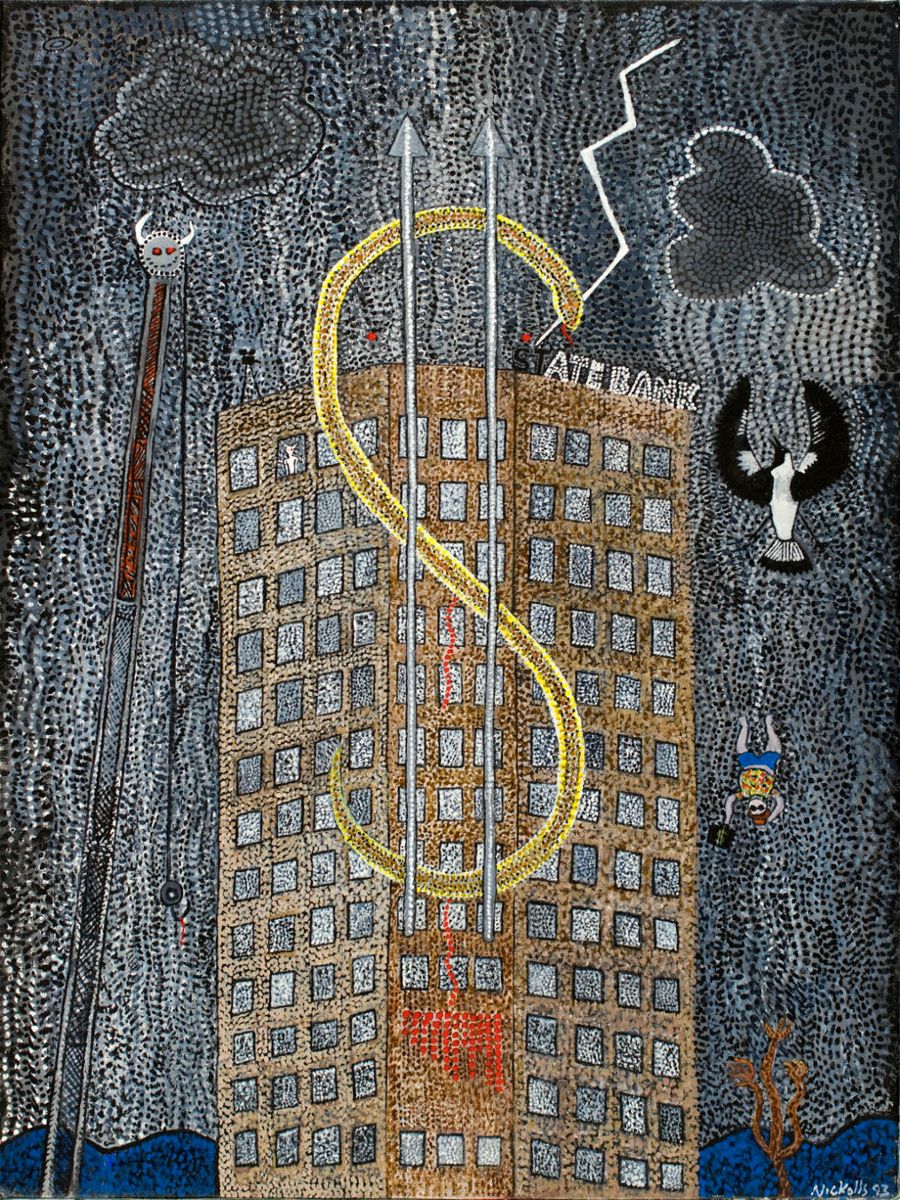

Osborne’s analysis of the 1980s and 1990s as a "post-modern moment" in the eponymous chapter captures the era's ethos of abundance and innovation. Amid the rise of the creative industries phenomenon and the proliferation of curatorial activities, she maps the emergence of artists including Annette Bezor, Hossein Valamanesh, Anna Platten, and Ken Orchard who for Osborne, epitomised the spirit of the age—and place. Chapters dedicated to individual artists, such as Polish born Stanislaw Ostoja-Kotkowski and Ngarrindjeri Trevor Nickolls, provides further depth and insight into Adelaide's artistic landscape, highlighting the contributions of key figures to the city's cultural heritage. Similarly, Michael Newall's chapter on Adelaide's "A-Team" offers a nuanced portrait of the city's alternate and institutional art scenes, shedding light on lesser-known artists, teachers and movements that contributed to Adelaide's cultural vibrancy.

However, the record is not flawless. The accuracy of some entries, such as incorrectly citing Hetti Perkins as a co-curator of Brenda L Croft’s Beyond the Pale: 2000 Adelaide Biennale of Australian Art, (p361) highlights the need for sharper research and verification. And curiously absent from the record is the groundbreaking exhibition Illusion and Reality curated by Peter Timms, John Stringer and Elwyn Lynn at The Art Gallery of South Australia in 1977. [2] Illusion and Reality showcased contemporary art from America and Europe, offering a refreshing departure from the prevailing British influence and the didacticism of local currents at the time. Featuring a diverse array of conceptual art with mixed media, installation, and ceramic objects, the exhibition was a significant cultural event of its time, deserving recognition within the historical narrative of Adelaide's art scene.

To argue that Adelaide should not be viewed merely as a follower of national or international trends, for example, “an a priori assumption …(that) Adelaide was no more than a microcosm of that macrocosm”,[3] is not in accord with historical fact. As with all necessarily selective anthologies of this type, we see some artists cosseted while other artists, arguably ahead of their game, are not included. And while initiatives such as the Women’s Art Movement and the Experimental Art Foundation are portrayed as a "distinctively Adelaide initiative”[4], similar movements emerged elsewhere before Adelaide—which does not diminish the value of Adelaide's contributions. Rather, it suggests that Adelaide was attuned to worldwide movements and acted similarly to like-minded cities nationally and internationally.

The Adelaide Art Scene: Becoming Contemporary 1939-2000 offers a valuable contribution to the study of Adelaide's art history providing a rich and nuanced portrait of Adelaide's art scene, offering insights into its evolution, challenges, and triumphs. Given the variability of archival sources, some images lack impact, but overall there's an impressive range of colour illustrations brought together across the book. Through a meticulous examination of historical events, key figures, and artistic movements, Osborne constructs an account that challenges simplistic narratives and celebrates the diversity and complexity of Adelaide's cultural heritage, and the reader is offered a compelling argument for regional diversity and inclusion in the narratives of Australian art history.

Footnotes

- ^ Margot Osborne quoting Bernard Smith, The Adelaide Art Scene: BEcoming Contemporary 1939-2000 (Adelaide: Wakefield Press, 2023), 11.

- ^ Peter Timms, John Stringer and Elwyn Lynn's travelling exhibition, Illusion and Reality, was shown at The Art Gallery of South Australia in 1977, also the Australian National Gallery, and five other galleries in Australia between 11 February 1977-15 January 1978. It was sponsored by the Art Gallery Directors Council with the assistance of the Visual Arts Board of the Australia Council.

- ^ Osborne, 9.

- ^ Catherine Speck and Jude Adams, “The 1970s: Progressive, passionate and provocative” in The Adelaide Art Scene, 242.