Bodywork curated by Erin Coates for Fremantle Arts Centre offers a loose take on the subject of human plasticity. It presents works by Amber Boardman, Tarryn Gill and Kaylene Whiskey in which bodies are shaped by internal and external forces in curious ways. Refreshingly, it’s an exhibition without an overt manifesto that reserves moral judgements, allowing for flights of speculative fancy, multifaceted interpretations and moments of frisson between the artists’ works.

Amber Boardman’s impasto paintings are thick and goopy in places, with cartoon colours cast in a muddy tone so that depictions of flesh, mostly white, recall areas of the body close to its openings. Boardman’s career in animation specifically for the fun-gross “night time identity” of the US Cartoon Network, Adult Swim – is often-cited as an influence, and with good reason. Figures are pictured in various stages of distortion or bodymelt, pressed together or with the air between them full of heavy energy. In Familial Triangulation/Field Day Event (2018) a man and a woman – presumably a mother and father – and an adult-baby figure are joined by the mouth, heart and brain with ropes of colour that knot them into a single family unit. This symbiotic togetherness is far from wholesome, more like an emotional human centipede.

The Internet of Vibes (2020) is an irreverent street scene full of dancing people popping open in chunky bursts, cracked apart as though by lightning bolts or emotion, like a scene from the film Eraserhead. Similarly, Be Your Own Plastic Surgeon (2019), Makeup Bus Commute (2015) and Spray Tan Research (2018) show messy figures likely to be female in thrilling pursuit not necessarily of beauty, but of change and new knowledge. These figures are, in Boardman’s words, artists working with themselves as medium. Two large-scale loosely gridded paintings, less psychologically porous and evocative than her overtly figurative works, offer formal character studies of the colours and shapes of dating apps and porn sites.

Tarryn Gill’s s Limber I, II and III loom ceiling-high and stretch gallery-wide, a dream-like sculptural blend of calisthenics poses Gill learnt as a performer and the reaching branches of Trembessi trees encountered on residence in Bali. Viewed in the round, each angle reveals a new contortion of multiple arms and legs. Gilded fabric skins are stitched Frankenstein-style in fragments over foam musculature. The central figure, its mid-leap soar grounded by a too-long leg like a kangaroo boxing on its tail, is embellished with long fringe-like blonde hair. Both title and form speak to their dexterity and skill, their evident strength and power, posed in places as though their whole weight is borne on a single foot.

At the opening, artist and curator Anna Louise Richardson pointed out that while Gill’s sculptures have previously been all face or head, these new forms – the largest Gill has ever made – were all body. She’s right. Eyes are embedded in knees and folds and the crevices between legs, holding the gaze from every angle, but the consciousness suggested by those eyes appears to have no central control. They radiate a pure, egoless confidence.

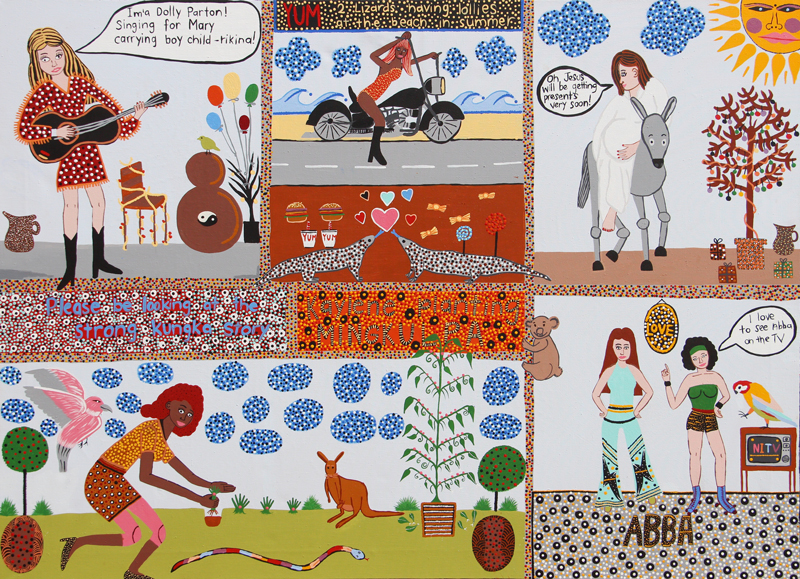

Kaylene Whiskey’s paintings, prints and short video work introduce a cast of characters at work and play in the remote Aboriginal Community of Indulkana. They include Kaylene herself, Cher, Dolly Parton, Michael Jackson, the Virgin Mary, Tina Turner, a white boy trying to steal mingkulpa (native bush tobacco), Skeleton Man, Wonder Woman, Cleopatra, and an unnamed cast of glamorous friends, among others. Whiskey often breaks paintings down into multiple cells on a single canvas, each surrounded by dotted patterns like comic strips or religious icons, an atmosphere of reverence heighted by a spotlights in a deep blue room. Her eye for detail is whimsical and sharp: boomerangs are crossed above Christmas trees, a water snake rains down on a quandong tree while Cher advertises mingkulpa for sale.

In Strong Kungka Story 1 & 2 (2017), a parrot dances to ABBA on top of a TV tuned to NITV while a white boy with John Lennon glasses and a goatee interrupts a birthday celebration at the art centre with his protest sign: “BLACK LIFE PALYA”. Elsewhere, Dolly and Cher receive the loving treatment of individual portraits, the latter in a costume celebrating her own Indigenous heritage. Whiskey’s paintings contain the barbs of what she refers to as “hard stories” and hint at Tjukurpa (cultural stories), and they are full of joy and great outfits. They acknowledge and celebrate the centrality of Black, female and working-class creativity in what is casually, and often diminishingly, termed “popular culture”. This is a plasticity not solely of the body but of time and social space, where costuming, imagination and the force of fandom create a powerfully malleable world studded with stars who are friends and peers, everyone raised together on a glittering pedestal.

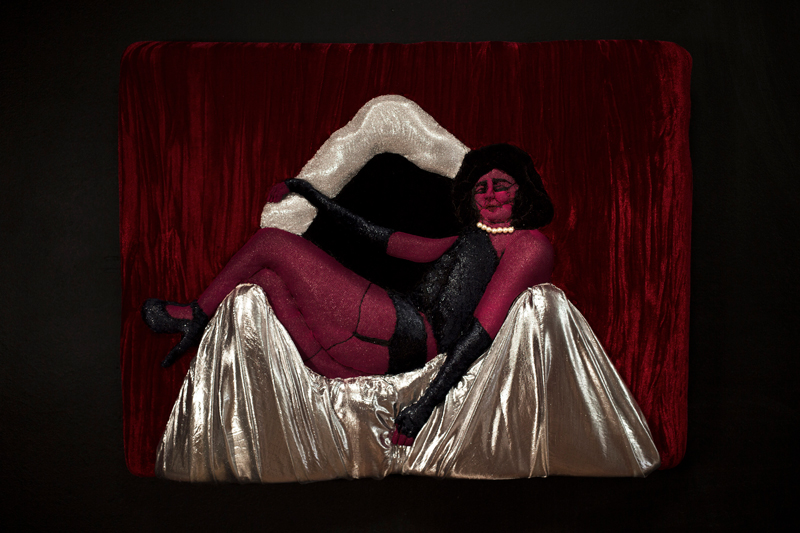

Sharing Whiskey’s blue room are a sequence of sculptural reliefs by Gill, under the series title of Show Girl. Each is an assemblage of velvet, satin and beading depicting formative “role models” caught in pose or repose: Miss Piggy, Jessica Rabbit, Dr Frank-N-Furter and Janet, the Rockettes. As in Whiskey’s paintings, combining references to both fictional and real-life figures opens the door between realms and allows characters to move freely. Gill’s choice of the term “role-models” is telling, a positive affirmation that frames the playful, sexy glamour of each figure as aspirational, exuding as Whiskey’s paintings do the holistic embrace of a true fan. Terms like “popular” and “fandom” – rather than the more neutral “influence” – suggest a hierarchy of value. “Influence” allows for critical appraisal and self-awareness.

Fandom is an obsessive, imitative cult of personality with an explicitly gendered variant, the fangirl. Note the difference, for example, in the statements that: (a) Amber Boardman’s paintings appear to be influenced by depictions of women in modernist painting, recasting squalling De Koonig-esque monsters as agents of their own destiny; or that (b) Amber Boardman’s cast of cartoon-like, morally ambiguous characters suggest she is a fan of Phillip Guston. The Bodywork universe intersects with others aiming to reclaim fandom: for example, director Jessica Leski’s documentary I Used to be Normal: A Boyband Fangirl Story (2018); and Yve Blake’s Fangirls, the Musical (2019) – as a profoundly self-reflexive and generative process.

Bodywork discards this and so many other assumptions that are either explicitly or implicitly gendered: that an interest in celebrity and fashion is vacuous, that a women’s experience of the body is inherently pathological, that choosing to modify the body is a symptom of victimhood, that glamour and innovation belong to the city, and that there is an ideal beauty and a monstrousness independent of cultural conditioning. Such ideas can feel natural, absorbed as though through a cassette recording while sleeping, but they dissolve rapidly enough with the sharp consciousness of daylight. It’s an exhibition free of the dissociative pathos of the abject and from the sourness of shame, that acknowledges the complexity of surface and the strength of the differently shaped. It’s also an all-women exhibition that posits the artists’ lived experience as women as one influence intersecting with many others, allowing them to be artists rather than women artists.

I wonder at the relationship between Bodywork and curator Erin Coates’ own artistic practice. Coates is an avid and disciplined rock and urban climber with an encyclopedia knowledge of cinematic body horror, interests that have manifested as artistic projects in various ways, frequently as collaborations with other women. Between these interests is a fascinating interplay between control of the body and its opposites. The Pact (2017) celebrates the physical dexterity of two female climbers – Coates and longtime collaborator Shevaun Cooley – and the bond of friendship between them. The unfolding dialogue of movement between the two climbers is worked into an elegant formal language of choreography, shape and colour in series of videos, drawings and still images.

Coates’ short film, Dark Water, 2019 made with Anna Nazzari and shown in Leigh Robb’s Adelaide Biennial, Monster Theatres at the Art Gallery of South Australia earlier this year, is a deeply triggering body horror narrative infused with matrilineal grief and the psychic undertones of a complicated relationship with reproduction. in her curatorial essay for Bodywork Coates references Barbara Creed’s argument for the female reproductive body as the prototype for popular depictions of the monstrous in horror, a challenge to the role of women as victim and a vehicle for exploring female agency and power.

Horror is a genre, even when full of glee, with an ambivalent and often ironic relationship with redemption and Dark Water ends without resolution, aiming to unsettle. Many of Coates’ projects – even The Pact, with its emphasis on trust and kinship – end on this note, with lone figures or isolated duos fighting for survival or to build a new and better world in scenarios with a darkly post-apocalyptic inflection.

Human plasticity and its representations, or explorations of how other bodies come in through our eyeballs and manifest in our lives, can easily acquire an air of the apocalyptic or be shaped by distrust. Perhaps it’s the circumstances, perhaps its being back in the gallery after a long pause, but the atmosphere of Bodywork feels in contrast to be one of quiet but pervasive celebration, even in its weirder moments of gore and porn. For all its strangeness, it feels not so much unheimlich but more curiously like a warm and familiar embrace, an affirmation of difference – the incomplete and the unsettling, difficult and beautiful experiment of living inside a body in dialogue with other bodies.