How to start talking about a biennale, let alone how to start making one? Rather than starting with a big over-arching idea, why not let it grow out of what is presented to you. Parallel Collisions begins at the front entrance of AGSA, all the way through the Elder Wing, then you're turfed out into the gallery to find your way back to the Temporary Exhibition Galleries. Then you travel in the opposite direction until you exit the show through a white geometric cave with a small white door. It’s an uncompromisingly specific experience.

I’ll play my cards straight up and say I was moved by Parallel Collisions.

Alexie Glass-Kantor and Natasha Bullock haven’t been afraid of adopting a deliberately non-prescriptive approach to talking about the exhibition in publicity opportunities. What’s clear from the press releases and interviews: the biennale isn’t a survey, it is artist-led in conception, it isn’t about presenting a group of the latest, hot-right-now artists packaged up in a svelte, slick, 'Contemporary Art’ exhibition. It would be naïve to ignore that some of the artists are pretty hot-right-now, but if Parallel Collisions reeks of anything it’s integrity.

Snaking through the Elder Wing are a series of "incursions" and “re-duxes” - either works which have been specifically designed to infiltrate the traditionally hung permanent collection or re-visitings of previous works by artists. The redux model works well, drawing out the trajectories of individual practices rather than emphasising the presentation of a singular product. Some are more successful than others. Tom Nicholson’s excavation of H.J. Johnstone’s Evening Shadows paired with his presentation of Centenary of Cummerangunja archival footage contribute strongly to the exhibition’s recurring discussion of how activist energies can be renewed in Australia. Both Nicholson’s work and Richard Bell’s wall painting of Olympic athletes and civil rights activists Tommie Smith, John Carlos and Peter Norman manage to invoke the spirit of the past events they refer to – re-echoing strong moments in the history of black activism. The work has the potential to reverberate the spirit of positive actions from the past into the future of activism in Australia.

Rosemary Laing’s series of photographic intrusions into colonial landscapes are less strong. The initial work – groundspeed (rose petal) #17 – is lush and disturbing. The other images scattered throughout the exhibition – involving a large wooden structure superimposed onto Hans Heysen style landscapes – were a bit dull. Perhaps the presence of the actual structure would have been more powerful. Much celebrated Australian artist Shaun Gladwell’s contribution in the Elder Wing felt flat too – the physical presence of the work doesn’t quite match the exhibition guide rhetoric about piracy, authenticity and ambiguity.

The decision to place works within the existing collection was risky – it easily could have resulted in a very cheesy install. For the better part, predictable reflections on the collection were avoided and interesting rapport sparked up between temporary and permanent works. Tim Silver’s shiny black burls – Untitled (trauma 3, 4, 5, and 6) – and the hypnotic movement of Susan Jacobs’ snake in Snake drawing both echo Hans Heysen’s smooth, snaking young gums more successfully and unexpectedly than Rosemary Laing’s after Heysen. Philip Samartzis’ Microphonics – an aural recording of the gallery made in 2011 and replayed in the space in 2012 – is at times plainly disruptive, piercing through the particular kind of peaceful silence the high-ceiling Elder Wing creates. But then at other moments it seems to intensify that peacefulness, and turn the entire experience into something almost hypnotic.

The reviews of Parallel Collisions thus far – John McDonald in the Sydney Morning Herald and Christopher Allen in the Weekend Australian – suggest the show’s greatest weakness is Bullock and Glass-Kantor’s tendency to talk about the exhibition in an ambiguous, floral, conceptually-flaccid kind of way. I’m not convinced by this argument – I’m no fan of formless art-speak, but it seemed to me that Bullock and Glass-Kantor’s writing in both the exhibition guide and accompanying publication was both lucid and capable of conveying the inherent physicality of the exhibition and its rhythms. Rather mimicking the experience of reading a well-argued essay – as many curated exhibitions seem to – Parallel Collisions feels experiential and emotionally complex. Its power is corporeal, affecting you until you think with your body. Like a really good song.

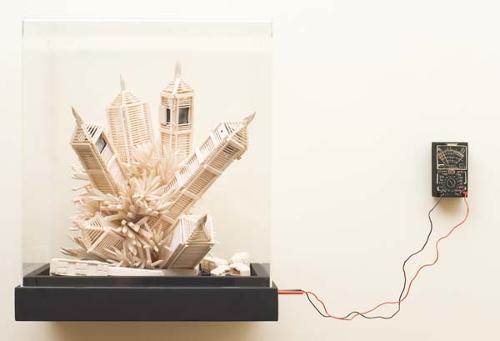

Pat Foster and Jen Berean’s Unity and fragments (how to be alone) – which you will encounter as you lower yourself into the Temporary Exhibition Galleries down the staircase – has both white-hot elegance and a bizarre sense of humour. The silver steel structure hangs from the custom-built ceiling, parallel with the half-way landing on the stairs. Hanging upside down from the grid is a piece from the permanent collection – Gerrit Rietveld’s Zig-zag chair. The effect was something I’d call minimalist slapstick. On the wall behind Unity and Fragments is Marco Fusinato’s Double Infinitive. On second viewing the vibration of the giant dot pixels subtly foreshadows the intense explosive motion of the Fusinato work you will encounter later in the show - Imperical Distortion. This tendency for works to resonate and reverberate with each other and with the space is a huge strength of the show. The recurrence and disruption of patterns within the show – and the consequent commentary on the place of time, the past and the future in contemporary art – rejects the craze for the newest new and the easily packaged. In this sense Parallel Collisions contrasts with the flashiness of AGSA’s 2011 Saatchi: British Art Now exhibition.

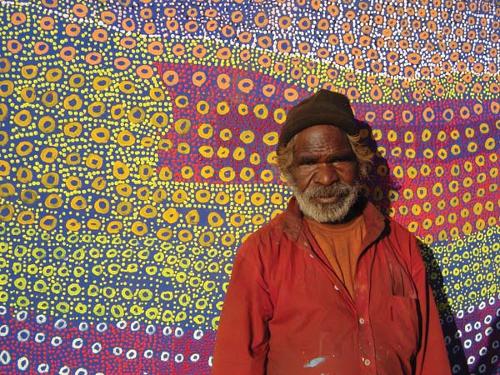

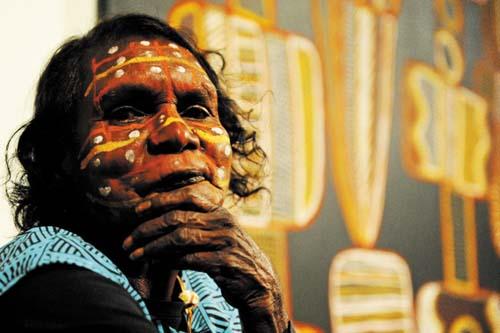

In the last section of the exhibition there are a number of artists presenting remarkable objects – particularly Michelle Ussher, Rob McLeish, Ricky Swallow and Timothy Cook. Ussher’s canny use of painted porcelain on a soft velveteen surface recalls Louise Bourgeois – particularly where the porcelain imitates panels of plaster and bandages, hastily sewn together to make misshapen heads. McLeish’s wet, gestural sculptures provoke disgust in a way that only the human body can. Swallow’s modest casts of folded cardboard objects feel kitsch but happily so. You can sense the pleasure the artist has taken in making these works. Cook’s paintings and carved burial poles – Kulama and Tutini – are visually bold and exciting, defying the false imperative for the contemporary to break with the past rather than draw strength from and invoke the relevance of traditions.

Exiting through Stephen Bram’s stark white warped-perspective room – Art Gallery of South Australia, north wing, basement – your senses are cleansed, re-oriented for experiencing the real world. If curating has a future – and it does – Bullock and Glass-Kantor’s approach needs to be noted. Not illustrative, but responsive and generative. If exhibition-making is to become a practice in its own right, it must become an explorative process, as art-making itself is.