It seems odd that this travelling exhibition should be so sturdily confined to the urban east coast of New South Wales. Callaghan may have established his reputation at Sydney University's Tin Sheds and at Wollongong, both in New South Wales, but his work is of national importance, and this survey really should be spreading its wings to other states.

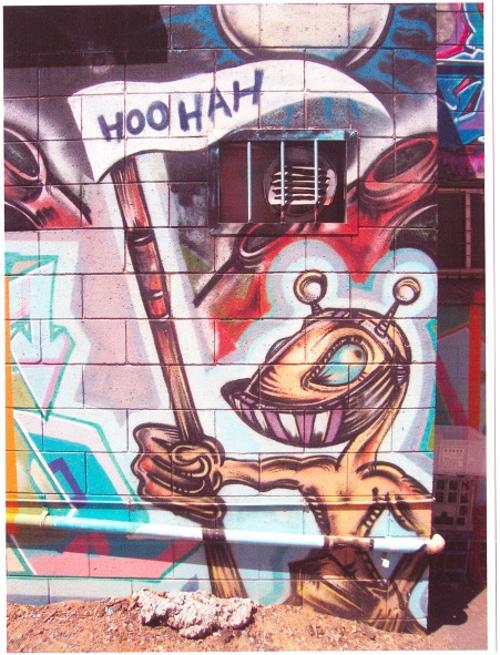

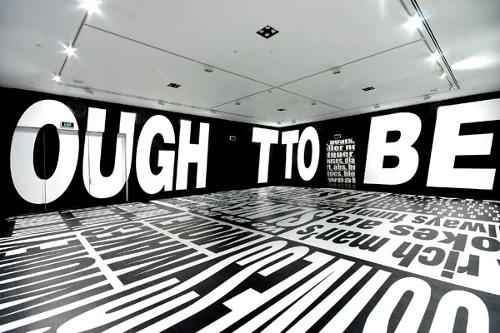

Callaghan's work is so ubiquitous that it can be a shock to realise how much he defined political poster art in the late twentieth century. The exhibition opens with one of his posters made with the Earthworks Collective at the Tin Sheds - Give Fraser the Razor. This crude cutting edge image was plastered all over Sydney by those who responded to the sanctimonious response to the fall of Whitlam. But in chronology the exhibition starts much earlier with the concrete poems the young Callaghan made with Phillip Batty and others for Box magazine in the late 1960s. The concrete poems, made on typewriters and distributed via a roneo machine with the aid of the local Presbyterian minister, hint at a layer of Callaghan's intellectual heritage which is not addressed in this exhibition. The poems address images of war (they were written at the height of the protests against the Vietnam war) and show a surprising visual sophistication for a Wollongong schoolboy. In the social hierarchy of geography Wollongong speaks of working class culture, the vernacular of the proletariat. However Callaghan comes from the class of child who accompanied parents to an extended journey to Europe at the age of twelve, who has access to office typewriters, a child of the local intelligentsia. He therefore has the self-confidence to make radical gestures.

After his time at Earthworks, where he adopted their characteristic John Heartfield influenced composition, Callaghan returned to Wollongong where he founded Redback Graphix. Here he developed his idiosyncratic style, mixing fluoro pinks, yellows and greens with intense black outlines. There is deadpan humour in the Greetings From Wollongong series of screenprinted postcards. The early 1980s was a time of economic recession and Wollongong had been hit hard. So the caption on one reads Born Free: on the dole, your consolation prize. Visually many of the works of this period owe much to Maoist propaganda art of the 1970s, some of which had toured Australia. They have the same clear colours, similar groupings of figures with fists raised to the sky, or arms outreached to enclose the viewer.

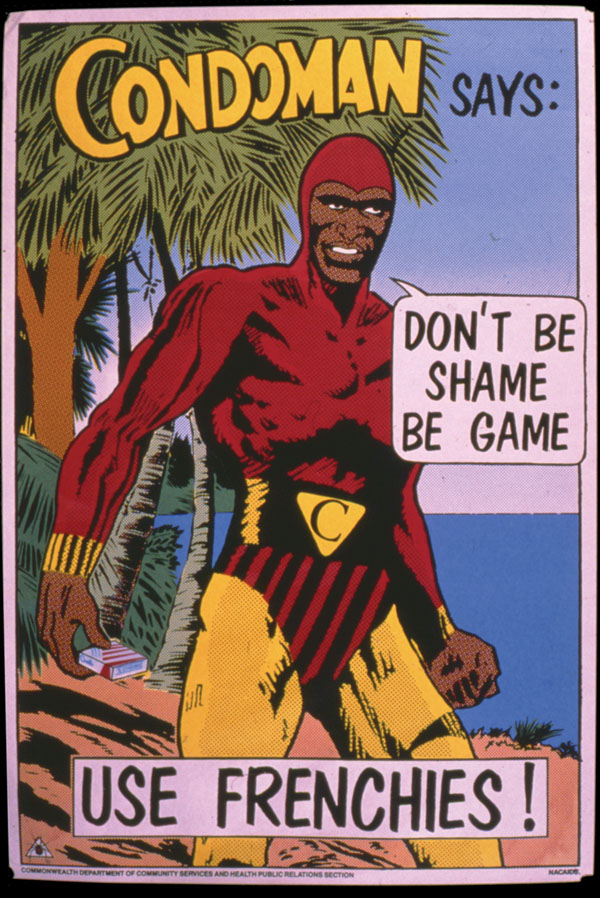

Throughout the 1980s and 90s Callaghan moved towards undertaking official commissions from a number of Commonwealth government departments. He is the creator of Condoman the Phantom-like figure who advocates the use of condoms for young Indigenous men, one of the more successful anti-AIDS health campaigns in the Northern Territory. He also made a series of narrative images on alcohol abuse, again aimed at convincing the Aboriginal community to change their behaviour. Visually these owe a great deal to Robert McPherson. This is indeed Callaghan's talent in his graphic work, his ability to appropriate elements of others' styles and turn it to his own purpose.

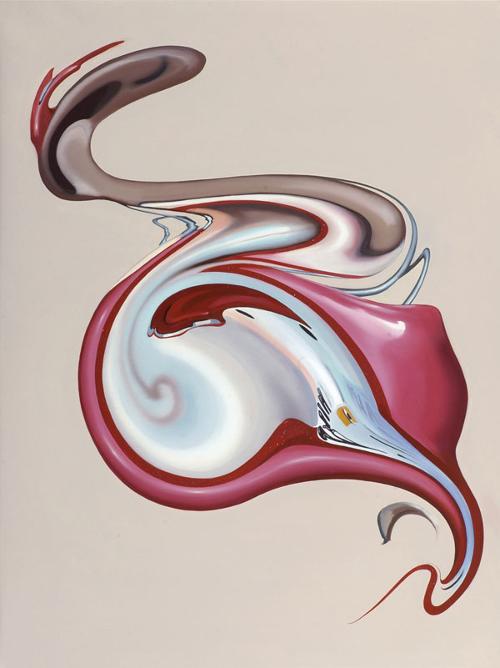

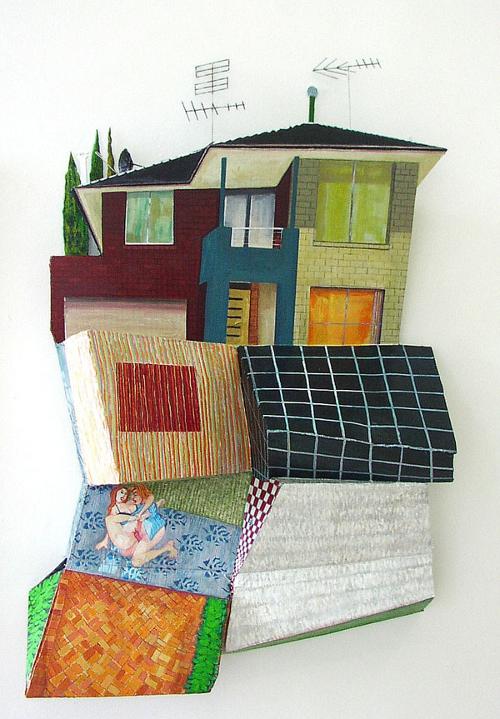

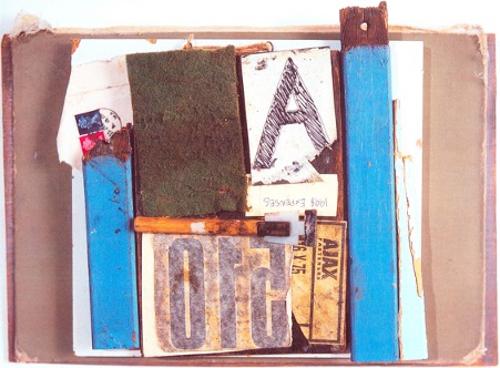

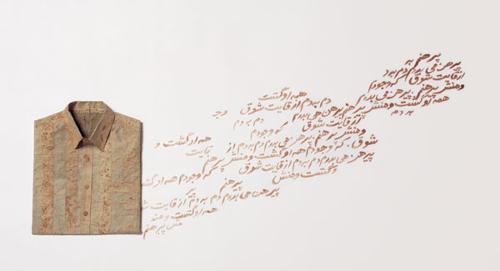

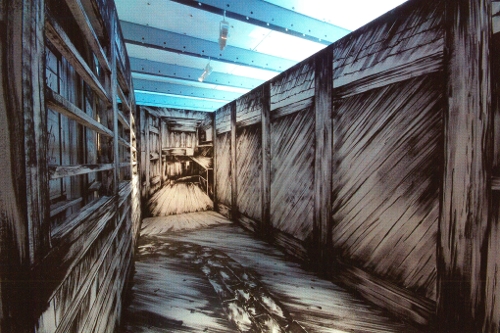

In recent years he has turned away from commercial graphic design to making paintings and sculpture. The imagery here is based on death or rather those dry bones that remain after flesh has rotted away. The paintings of the Flos Mori (Flowers of Death) and Memento Mori series are precisely made, in a smooth slick style that is reminiscent of hard edge paintings of the early 1970s. But layers of meaning are found in the sculptural works which use an assemblage of cut-out 'bones' with other objects, to create images of lives of the saints. Santa Lucia of Syracuse (who was blind) has eyeballs on a plate and a lamp, while Santa Chiara d'Assisi, patron saint of television, television writers, telephones, telegraph has bones that must listen to relentless day-time television, a concept far removed from the life of the original Poor Clare. In the end, when life is over, bones are also a part of the stories that become myths - exemplary tales from the dead, told to guide the living.