Accounts of Australian art history have changed from a narrative to a complex puzzle, from a linear account to an intertwined pattern as complex as those played across continents by gamers on the web. Once readers of books and visitors to art museums were presented with the certainty of Bernard Smith’s magisterial narrative. It started with a colonial Genesis, artists left the country to Exodus, returned and laid down the law with Leviticus. The chapters rolled out with all the certainty of the Pentateuch.

In the 1980s this world of certainty was challenged. When the National Gallery of Australia opened in 1982 Daniel Thomas incorporated Indigenous art into the Australian galleries, a reminder that Australian visual culture never existed in a terra nullius. Then in 1988 this challenge was extended with the Great Australian Art Exhibition a loint project of Thomas and Ron Radford which challenged the notion of a singular linear narrative of art. The most dogmatic of the new histories was by Tan Burn and the writers of The Necessity of Australian Art, a deconstruction of the ways past art historians, especially Smith had looked at our visual culture Meanwhile Joan Kerr and her many volunteer researchers were working at a more subversive and ultimately more enlightening project. The publication of a working paper in 1984 was followed by The Dictionary of Australian Artists: Panters, Sketchers, Photographers and Engravers to 870, published in 1002 and Heritage in 1995. The multi-layered panorama revealed by Kerr and her tear of researchers served to completely redefine 19th century Australian visual culture. This surely was a more potent challenge to Bernard Smith's historiography.

But nothing is as it seems.

Bernard Smith’s Australian Painting in 1962 had as one of its foundations Smith’s own 1953 catalogue of Australian oil paintings in the Art Gallery of New South Wales. This extremely useful publication contained concise dictionary entries on many previously unrecorded Australian artists. In 1973 Bernard Smith had undertaken to produce Australian entries for the revised version of the Thieme-Becker Kunstlerlexikon [Dept of Fine Arts archive, University of Sydney archives]. This project had later transformed into the Dictionary project that, after Smith’s retirement, was taken on by Joan Kerr. Even supposedly linear histories backtrack and cross paths.

Legacies.

In the two years since Joan Kerr’s death her pioneering work in uncovering histories of Australian art has become the foundation for a new generation of Australian art historical research: The Dictionary of Australian Artists Online. The editor-in-chief, Professor Vivien Johnson, was nominated by Joan Kerr as her successor, and is encouraged by Bernard Smith. Johnson’s Aboriginal Artists of the Western Desert is, with Kerr’s book, one of the foundation works for the DAAO.

The most significant shift in researching, writing and teaching Australian art histories in recent years is the recognition of the centrality of the nature of Aboriginal culture to Australian experience. This change is recognised in the debate on ways and means of teaching narratives of Aboriginal art in universities, both to Indigenous and non-Indigenous students. The hunger students have for knowledge of Aboriginal art is sometimes in marked contrast to attitudes to other Australian art histories.

At some universities, notably The University of Adelaide, students are able to integrate their studies with the collections of a supportive state gallery. Others concentrate on more theoretical concerns. In all cases the study of Australian art history intersects with the way universities in general and the humanities in particular are dealing with the Chinese curse: ‘May you live in interesting times’. Every day in every way, more must be made from less. Class sizes rise; resources and courses are dropped, even while scholarship expands. Some universities have transferred their art history courses to art and design schools. Others have joined in the general throng of amalgamated disciplines.

It is easy under these circumstances for what is seen as a subset of a minority discipline to be ignored. Yet Australian art history is one of the rare fields where even undergraduates can experience the thrill of primary research. It is also closely embedded with questions of national identity so that when our sense of self is coloured with beetroot-red shame, then those writing on art can move out of the academy to the popular media and join the national debate.

This issue of Artlink presents some of the ideas and issues that concern Australian art histories today. Universities are like the mills of God. They may grind exceedingly small, but they move slowly. Before courses can be taught, the field needs to be researched. Scholarship needs to be published. Otherwise we sell ourselves (and our students) short. Because book publishers have long preferred superficial illustrated surveys over scholarly analysis, those writing on Australian art have long been overly dependent on exhibition catalogues as a vehicle for publication. This has skewed the nature of published scholarship towards established taste.

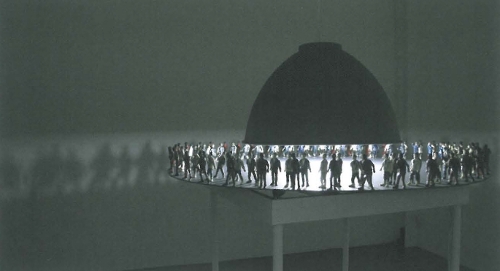

Salvation has now come in the form of the World Wide Web. There are many online projects based on the premise that access to information needs to be kept in the public domain. The Australian Digital Theses Program will eventually secure access to PhD theses on a range of topics, the Australian Dictionary of Biography is also going online. The Dictionary of Australian Artists Online (DAAO) will in time expand from Kerr and Johnson’s original project to enable both research and future publication in a way undreamed of a generation ago.

The future is another country. Art will be made differently there. But it will be made, noticed in its making, written on and discussed.